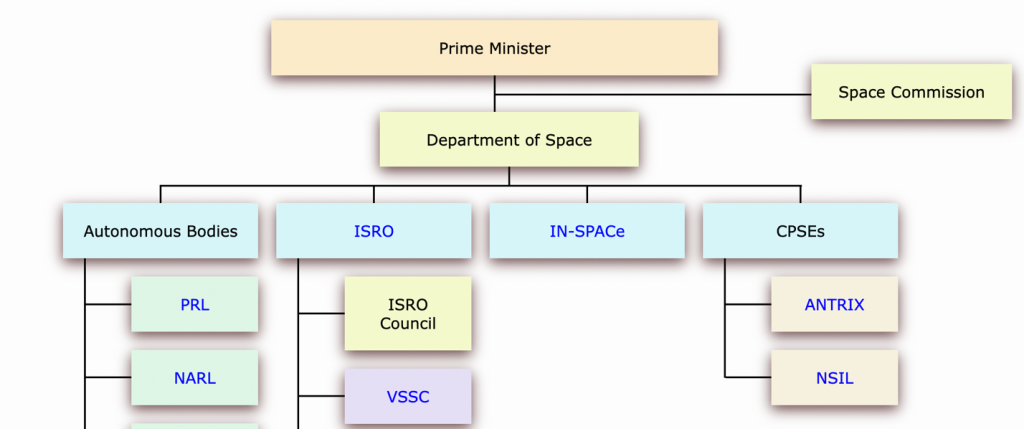

This is not to say that there is no scope for improvement. For instance it has been pointed out that IN-SPACe should not be under the Department of Space, mechanisms to handle disputes must be put in place, and the policy must be further crystallised as a legislation. However it is impotrant to draw attention to the significant shift undertaken in a sector which has traditionally been dominated by one large public organisation, ISRO, with a long-standing public perception of being a high performer.

The key takeaway for me here is the new institutional design: clarifying the roles of institutions relevant to their core expertise; encouraging private sector participation and carving out new institutions for achieving larger objectives.

There are learnings from these developments to the institutional design of other sectors. I will dwell into those for our law and justice system. Not much attention has been paid to how institutional design affects the rule of law in our country. The popular discourse is dominated by demands for capacity enhancement (more judges, more courts, more forensic labs), debates on who appoints whom, and since the COVID pandemic, on using technology. Given the large complex system that the law and justice system is, in addition to the above, there is also a need to view with fresh eyes the mandate of all the institutions involved in ensuring the Rule of Law, their processes and practices rules they follow, and their manner of interaction with each other.

Let’s take forensic labs for instance. For some years now many have flagged how delay in obtaining reports by forensic labs has affected justice delivery. This is the situation across the country. The Union Government is expected to spend about Rs.4500 crores over the next 4 years to enhance the quality of existing labs and establish new ones. This is especially important given that the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita and the Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam that have come into effect from July 2024 have rationalised and expanded the role of electronic and digital evidence. However, there is no indication of how private forensic labs could be leveraged for timely justice delivery. As has been pointed out, engaging with private forensic labs would require regulating them to ensure quality and compliance with professional and ethical standards. This would require a higher level of engagement by current institutions such as the directorate of forensics, the police, the prosecutors and the courts.

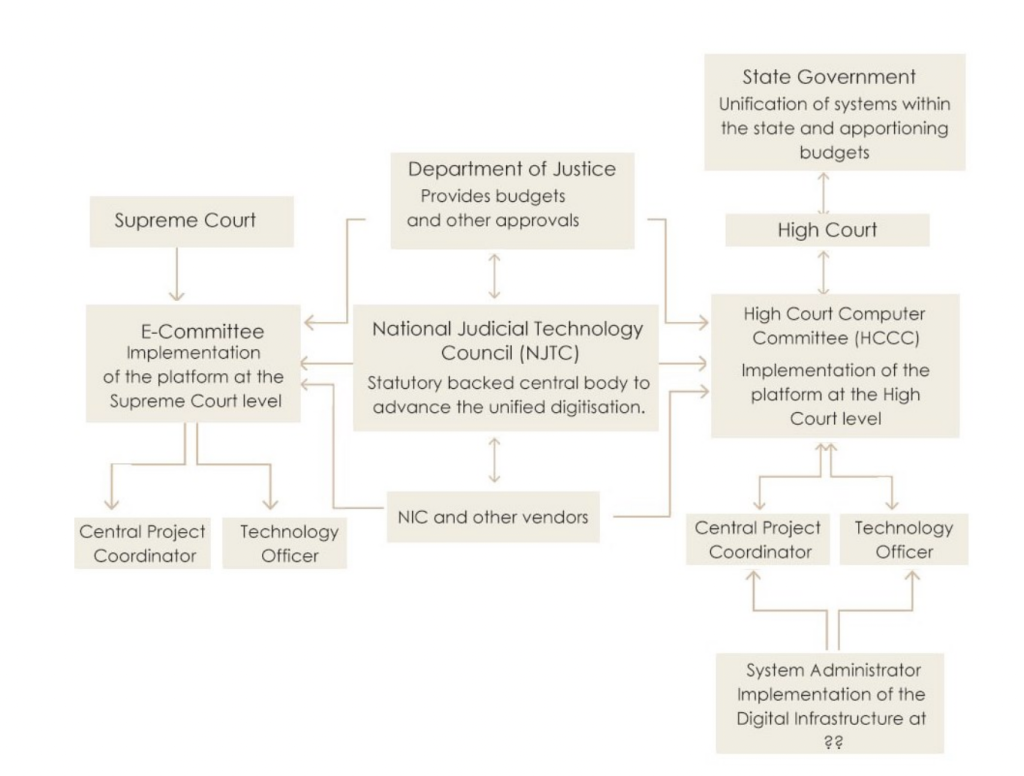

The situation is similar with technology. In 2023, the Union Cabinet approved Rs. 7210 crores for eCourts Phase III for the technological transformation of courts. Based on the radically transformative vision for the Phase III, the main objective of the Phase-III is to build digital courts “which will provide a seamless and paperless interface between the courts, the litigants and other stakeholders.” This is being implemented under the partnership of Department of Justice, Government of India, eCommittee, Supreme Court of India, in a decentralised manner through the respective High Courts. State governments are expected to supplement funding for eCourts Phase III.

It is critical that policy makers in the government and the judiciary think through how private players could be engaged actively to make this a success. This would require enhancing the capacity within the judiciary in writing out clear Requests for Proposals, tendering, contracting, quality testing, and tackling any performance issues (imagine the plight of a vendor who has to face proceedings in a court against or by the same court!). Capacity enhancement would involve, among other things, bringing on board (preferably as full-time staff or at least as consultants for the medium term) specialists in various aspects of technology implementation like system architecture, coding, designing user interface and user experience, change management, and project management. High Courts should set up Technology Offices headed by a technology expert.

The vision for eCourts Phase III had also envisaged the setting up of a permanent entity backed by a statute: the National Judicial Technology Council (NJTC) (see Institutional And Governance Framework under Operationalising Phase III of the vision for Phase III). A extract of the schematic representation of the institutional structure as provided in the vision document is shared below: