Ctrl+c and Other Stories.

In the process of unfurling our research method at The Rule of Law project it has been important to examine what data can help us frame information that can answer the question of what “delay” and “pendency” really means, outside of the anecdotal narratives that get thrown up both in the media and in reports of and by the courts themselves. If we were to generate statistics on the nature of judicial delay, what would we need to do?

My fellow travellers and guides Harish and Kishore, a few weeks into letting me roam the lands of literature review, came up with an ingenious solution.

Look to the cause list.

I’m fairly certain, after several months of speaking of cause lists with something like obsession, that the lay person in our country will know little or next to nothing about what a cause list is.

A cause list is produced daily by every court in the country, detailing the case number, the litigants, the lawyers, for the reference of those who are in the process of litigation. This is a public document.

The cause lists, however, are a kind of endlessly disappearing archive of information, since they are put up each day for the use of lawyers and litigants, and removed once their use passes. Beyond a certain amount of time (a week, perhaps a fortnight), these lists get taken off the main website.

A cause list is, on some enquiry, a straightforward document: it tells you which case is heard before which judge on what day. In this, it is very valuable, since each case number that is in process in the courts will necessarily show up at some point in a year, during the various stages of life in the courts. As we said in our last post, there are 44,56,232 pending cases in the High Court. The cause lists will ensure that we are able to capture these cases in our data in the coming year.

And most crucially, what we can capture with this information is the case number itself.

The case number is, for example, WP13457/2004. A Writ Petition, a number, and a year.

A typical cause list contains the following:

- Case Number

- Date of Hearing

- Judge

- Hall Number

- Court/Bench

- Advocates for Petitioner

- Advocates for Respondent

- Stage (for eg, Orders, Interlocutory Appeals, Preliminary Hearing.)

With each Case Number, we are able to access the following details:

- Date of Institution

- Date of Disposal in Lower Courts

- Case Status

- Causes of Adjournments.

- Number of Times Listed

- Details of what the case is listed for (for eg. Non-compliance of office objections, etc.)

- District of Filing of Case

How were we going to put this information together, everyday, across 24 High Courts of the country?

A woman’s best friend in such a situation is really manual data entry. We started our work by spending up to a week copying and pasting each element of the data available in the cause list into an excel sheet: a case number and all its corresponding details.

There is, for example, no standard format for the digitised PDF of the daily cause list that is put up on a High Court’s website. It is typically a type-written document, put together by a clerk, scanned and uploaded on to a High Court’s website as a PDF. A document that consists of scanned images of text is inherently inaccessible because the content of the document is images, not searchable text. Sometimes, these PDFs are not scanned images but rendered with html; copy and paste a single line of this into an excel sheet and you will be left with a glorious garble that breaks down the tentative coherence in format effected by that judicial clerk who has compiled the cause list that morning.

Each High Court, too, has different formats for the way a cause list is organised. Each daily cause list typically runs into up to 50 pages, ranging between 800 to 2000 cases before a few judges in a day.

I started with three High Courts: Karnataka, Delhi, and Gujarat. In the case of most cause lists, the process of copy and paste was fairly straightforward, since the PDF allowed for it. However, there were those cause lists whose PDF did not allow for an easy cut and paste of information. What I discovered was that while it took me about an hour and a half to put together details of 250 cases into an excel sheet from a PDF from the Karnataka High Court, it took me about two hours to put together merely 20 cases from a cause list of the Gujarat High Court.

It became quite clear from this exercise that this manual data entry would not only be inordinately time consuming, but that it was necessary for us to begin to understand what a large amount of this data collated could show us about possible inferences.

At this stage, we turned to the data entry elves at a small service provider called Data Con Services. Quite close to Toll Gate in North Bangalore, Data Con services is a small house converted into an office space full of cubicles, populated by young men and women typing away and keying in data, row by laborious row. Having spent some time keying in this information myself, I knew that this work involves a mixture of tedium and close attention.

Our data entry elves were able to collate and compile the daily cause list for four High Courts and managed to put together well organised excel sheets for 20 days of cause lists in the span of two months. By the end of November 2014, we had data for 80,000 cases in hand, done all by the force of pure manual labour.

While our team had spent a few months beginning to understand all the possible ways in which we could use the information in a cause list for our research, Kishore had spent his energy understanding the way the courts organised their data on the High Court websites. This proved to be an inordinately useful two-pronged approach, since our team was able to understand the ins and outs of the information even as softwares were being written to make the data available to us.

For example, our team undertook the task of picking a randomised data set from the Karnataka High Court of October 2014, to trace the date of institution for each case number. This involved another week spent with Ctrl+C, that gloriously simple yet tedious function: feeding in a case number into a High Court website, to trace it backwards and see when that case was instituted, and from which lower court it emerged. This process of tracing date of institution helped us understand that a simple case number points towards several layers of important data.

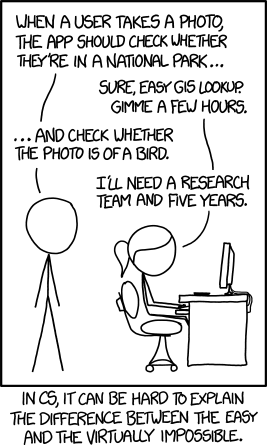

It was by this time that softwares that defy the imagination of an ordinary sociologist came into force. Kishore had cracked for us a method that parsed all the data on the High Court websites into clean and crystal clear excel sheets: what had taken us a few months to understand, a software broke down in a matter of mere seconds.

So it turns out that what we had considered virtually impossible, turns out to be possible. Armed as we are with a fast growing database, we will leave you again, to return later with more stories of our methods, of case numbers and case types and our ever growing, never ending relationship with excel sheets.

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author’s and they do not represent the views of DAKSH.

Kavya Murthy

RECENT ARTICLES

Testing the Waters: Pre-Implementation Evaluation of the 2024 CCI Combination Regulations

Not Quite Rocket Science

Administration of justice needs an Aspirational Gatishakti

-

Rule of Law ProjectRule of Law Project

-

Access to Justice SurveyAccess to Justice Survey

-

BlogBlog

-

Contact UsContact Us

-

Statistics and ReportsStatistics and Reports

© 2021 DAKSH India. All rights reserved

Powered by Oy Media Solutions

Designed by GGWP Design