Death Penalty

- Dr Anup Surendranath

- /

- The DAKSH Podcast /

- Death Penalty

The death penalty is a deeply polarising topic in India. People who justify and oppose it hold deeply held often emotional reasons for their views. Most of Europe has abolished the death penalty but India does not seem to be considering such a move.

In fact in recent years the clamour for capital punishment epecially for rapists has only grown louder. At the end of 2021 when this episode was recorded, the numer of prisoners on death row stood at 488, the highest in 17 years, according to the Death Penalty in India Report.

On Episode 6 we spoke to Dr Anup Surendranath who is the Executive Director of Project 39A (formerly the Centre on the Death Penalty) and an Assistant Professor of Law at National Law University, Delhi. His involvement with the death penalty our topic for today began in May 2013 by establishing and leading the Death Penalty Research Project that culminated in the Death Penalty India Report that was released in 2016. The project, first of its kind on the death penalty in India, interviewed all of India’s death row prisoners and their families towards developing a socio-economic profile of death row prisoners and also mapping their interaction with the criminal justice system. Today Anup joins us to help us unpack and understand how capital punishment plays out in India.

Show Notes

- Anup Surendranath,, Neetika Vishwanath, and Preeti Pratishruti Dash. “The Enduring Gaps and Errors in Capital Sentencing in India.” Nat’l L. Sch. India Rev. 32 (2020), 46.

- Craig Haney, Death by design: Capital punishment as a social psychological system. Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Craig Haney, Criminality in context: The psychological foundations of criminal justice reform. American Psychological Association, 2020.

- Jahnavi Misra, The Punished: Stories of Death-Row Prisoners in India, 2021Harper Collins

- Probal Chaudhuri, Debasis Sengupta and Paramesh Goswami, Adalat, Media, Samaj Ebong Dhananjoyer Phasi 2016.

- Project 39A, Death Penalty India Report, 2016 https://www.project39a.com/dpir

In the accused Naryan Kamde 865 is charged under Indian Penal Code Section 306 abatement of Sucide.Vikas Dubay is dead he’s been killed after an encounter broke out. This is the big breaking news that’s coming in. Suspense is finally over the Mumbai trial court today gave more with Momhamad Amin Cassab death sentence for murder and waging war against the country 17 months. The Consitutent assembly will frame the Constitution in terms of paragraph three of the resolution.

Welcome to the DAKSH podcast I’m Leah, I work with DAKSH which is a Bangalore based nonprofit working on judicial reforms and access to justice. In today’s episode of the Daksh podcast, we discuss the death penalty. It is a deeply polarizing topic in India, people who justify and those who oppose it often have emotional reasons for their views. Most of Europe has abolished the death penalty, but India doesn’t seem to be considering it. In fact, in recent years, the demand for capital punishment, especially for rapists, has only grown louder. Today’s guest is Dr. Anup Surendranath. Anup is the Executive Director of Project 39A, formerly known as the center on the death penalty, and an assistant professor of law at the national law University Delhi. In May 2013. He established and led the death penalty research project that culminated in the death penalty India report, released in 2016. Prior to this report, there was very little empirical information on the administration of the death penalty, including the uncertainty about the number of people India has executed, or information about prisoners who are sentenced to death. The project, the first of its kind on the death penalty in India, interviewed all of India’s Death Row prisoners and their families towards developing a socio economic profile of them, and also mapping their interaction with the criminal justice system. I began my discussion with Anoop by unpacking the term rarest of rare cases, and examining under what circumstances courts in India may award the death penalty.

So I think it’s often thrown about phrase with very little understanding of what it means, of course, there are certain offenses that are death eligible. In India, of course, a mandatory death penalty is unconstitutional. What does that mean that you can’t have an offense where the punishment is only the death sentence, you have to choose between life imprisonment or the death penalty, then the question is, how do judges choose. And this isn’t the punishment phase, of course, once you’ve been found guilty of your crime, and there is a framework that has been developed, in our judgment called Bachan Singh v. State of Punjab , but as to how judges should go about making this choice, and the Criminal Procedure Code makes it very clear that the death penalty is the exception. And life imprisonment should be the default punishment. And you if you have to give the death sentence, you have to record special reasons for that. And the court Bachan Singh v. State of Punjab tries to clarify this for the first time and says you have to look at aggravating factors, you have to look at mitigating factors, and then accord appropriate weight to each of these, and then see if the alternate option of life imprisonment is unquestionably foreclosed, then they say, in the rarest of rare cases, very often rarest of rare is understood as Oh, is it a rare crime, but if you read Bachan Singh v. State of Punjab saying it is more like you need to do it in as few cases as possible, it’s more of a numerical sense rather than a qualitative sense that it has come to a zoom in very common understanding. And I just want to point out that one of the factors that the court has listed in the mitigating factors, it is for the state to show that the accused person cannot be reformed.

So now let’s move to some famous death penalty cases in India. So let’s contrast the yakub Memon and Ajmal Kasab. So Yakub Memon was convicted for his involvement in the conspiracy behind a series of bomb blasts in Mumbai in 1993. With Memon’s case there were doubts about whether fair procedure was followed. You know, procedure requires that before a death warrant is issued, the lawyer of the person on death row must be heard. There should be a reasonable gap between issuing the death warrant and the date of the execution. These were not followed. It was also said that Memon had cooperated with Indian authorities on the assurance that he would not be hanged and this promise was not kept. On the other hand, Ajmal Kasab, who was convicted for being part of the November 26m attack in Mumbai, the case seemed much clearer. I mean, there were no such doubts about procedure. And it seemed like he had caught a fair trial. So tell us, Anup in your view why you would or would not support the death penalty in a case like Kasab’s?

Right. And I will answer that. And that’s often the big question, isn’t it in terms of anytime anybody discusses abolition of the death penalty? Oh, what about Kasab? Or what about the Delhi Gang Rape? Right? Those are the two big questions that are thrown at you when you talk about abolition, and I will address that, but I just want to make a couple of preliminary points. Cases like Kasab are not the norm for the death penalty, about the 130 140 death sentences that trial courts in India give out every year, you’re not seeing it for terror offenses, you don’t hear about a large number of the cases in which death sentences are handed out. And I think that’s part of the problem of the death penalty conversation, that the conversation tends to revolve around these famous cases, ignoring what is happening in the vast majority of cases that are not these cases, and we can discuss what what’s happening in those cases. Second, from the death penalty India report, very often you see that, oh, we need death penalty for terrorism. But if you look at India’s conflict zones, the death penalty is not used. And the reason for that is the state is doing something else there. The state is resorting to extra judicial and extra constitutional measures in those jurisdictions in those contexts, and I often think that, therefore the death penalty is needed for terrorism kind of thing is more of a facade really, right. It keeps the rhetoric going. Having said those two things, let me come to your question of would I support the death penalty focus up and undoubtedly, I just want to say that the lawyers who ended up representing Kasab particularly kind of worked with Mr. Raju Ramchandra, indeed, as amicus, he was appointed by the court to appear. It’s an incredibly tough case, those of us who remember the environment around and for a lawyer to stand up and argue that to do that service for the constitutional rule of law society that we are right, it’s not easy. And I think we need to acknowledge that effort, the kinds of arguments that were advanced, the kind of rigor and also in the Bombay High Court, Mr. Amin Solkar, who appeared, and these are lawyers operating under tremendous social pressure in this context, right. And then we often forget to acknowledge what they did. And we might have our own positions on morally what is required, right, in terms of I mean, I might feel very angry, I might be aghast at what was done. And I might have a certain moral response to it. But I think those in the legal system, right, judges lawyers have to say, what does the law require? And I think that’s where the proceedings in Kasab fell short that if you look at it, in terms of what the law requires, and the discussion on did the state show that Kasab cannot be reformed? And you might say, Why should we even care whether Kasab should be reformed? The law requires that, but just as Alam’s, opinion or judgment in Kasab answers the question of reformation. And then, of course, Mr. Ramchandran and raises that argument, he raises the argument of very young age of indoctrination. Mr. Solker also raises that argument in the Bombay High Court of indoctrination of age, and then this is just a foot soldier. Right? And it’s not some mastermind of this. But on the question, I think, for me, the thing was, did the state discharge its burden to show that somebody like him could not be reformed, just as alum resorts to saying that there is no remorse that’s shown, and therefore the inability to show remorse is then treated as being determinative, showing that this person cannot be reformed. Right. And that’s not how the law should be read or should have been read at that point. And that’s certainly not how the law has evolved after that, on reformation. And for me, that is a difficulty whether the state did not discharge its burden, really, and are definitely jurisprudence is lined with cases which say that the state wants to show that it wants to take somebody’s life it is upon it to show that this person cannot be reformed. You and I may like it not like it might say, Well, why should that be the position? It should not be that it should be something else. All that’s well and good, but that’s the law as it exists. And for me, that very crucial part of death penalty jurisprudence was not followed in Kasab’s case. And I think my moral position on it is are yours or anybody else’s is quite irrelevant in a legal proceeding, or even the judges own moral proceeding certainly should be relevant and saying what are the requirements of the law and what happened in court and I don’t think those requirements of the law were met. So moving away from you know, these high profile cases and

Going into the majority of cases that you refer to in your last answer. So can you just tell us a little bit about, you know, the background of death row prisoners, most of them, it’s the poor, it’s people who are from extremely marginalized backgrounds, very low levels of educational attainment, and having terrible levels of legal representation. Again, they’re quite counter intuitively, a large majority of them didn’t have legal aid lawyers in the trial court. And it was quite revealing to understand why there is this fear of the legal aid system and on the legal aid lawyer. And they feel this urge that they must do everything to try and get a private lawyer, right. And therefore, they get themselves into this further cycle of poverty and selling whatever or borrowing more money getting them into more debt, to try and get a private lawyer. But even then, just because they have a private lawyer, we are paying that person very, very little money. And therefore that doesn’t automatically ensure that just because you have a private lawyer, you’re getting good representation. So multiple axes of marginalization, on poverty, on caste, on education attainment, on access to justice, it’s not surprising that it’s the poorest and the worst off in our society that get the harshest punishment. And that’s true of every other retention jurisdiction in the world.

Another facet of this is you know whether we have enough safeguards in our justice system to ensure that no innocent person will get executed. And let’s discuss this in the context of the Dhananjoy Chatterjee case. And you know, whether these safeguards actually held up in that case, maybe you could just describe the case for our listeners. Before I get to that, I want to say that you don’t have to take my word or anybody else’s word for that we we did a study with 60 former judges of the Supreme Court on India’s criminal justice system and the death penalty. And it is very striking a vast majority of them acknowledged how a lot of our evidence is torture based, there is manipulation of evidence, there is planting of evidence by the police. And there was a widespread acknowledgement of the fact that there are multiple crisis points in our criminal justice system. But surprisingly, these very people, when asked the death penalty question, also then show very significant support for the death penalty. And that disjunct while acknowledging the crisis in the criminal justice system, while yet finding within themselves to support the death penalty is exactly what is happening across the country. Also, you know, everybody who I guess who’s listening to this podcast, does not want to do anything with the police, or the courts, we will avoid it. We ourselves don’t have faith and confidence in our criminal justice system. And we know how messed up it is. We know how violent it is. But yet, we are willing to rely on it to send people to the gallows. So that’s the broader context in this and Dhananjoy Chatterjee his case, he sentenced to death for raping and murdering a student in 12 standard, if I’m not wrong, in Calcutta, where he’s supposed to be working in this apartment building. And the prosecution’s case is that there’s some disagreement with the family. And this is sort of a revenge on that or whatever, right? Of course, there is massive clamor for his execution. And he’s executed on his birthday in 2004. What’s interesting, actually, is what happens after the execution, and the fantastic work that two professors at the Indian statistical Institute in Calcutta due on sort of reinvestigating this case, and the kind of inconsistencies in evidence and the loopholes that they pick up in the investigation in the trial, both in terms of very crucial pieces of evidence, like the button the chain in the flat, or this evidence that somebody saw Dhananjoy in the victim’s flat, and whether that person could have actually seen that Dhananjoy from that angle, and all crucial documentation of when he was actually, if at all fired from his employment with the service provider. A lot of inconsistencies that go to the very heart of Dhananjoy’s guilt on whether he was guilty at all. And a lot of suggestion that the investigation was perhaps manipulated and very, very strong suggestions of that, right. For those of you interested even want to watch the Bengali film called Dhananjoy, it really leaves you asking the question, right. And I think there has been very significant revisiting of public opinion on Dhananjoy’s case in West Bengal itself that, yes, maybe we got this wrong. And the point is, you couldn’t have executed somebody when there was so much doubt and that’s true of so many cases of people on death row. Sure. You might think there are cases where there is no such doubt. I’m not here saying that all cases have this doubt or any doubt, or whatever, but a very large proportion of cases are based on extremely dodgy evidence. That’s largely because they don’t have lawyers at that stage, initially, the investigation stage or at the pre trial stage, or even during the trial, where these things then get cast in stone. And that’s where the lapses happen the most. And that’s where you need the best legal representation and Dhananjoy’s case is one such tragic case.

And a lot of the outcry around the Dhananjoy’s case, you know, when when his trial was going on was around the alleged rape of the victim, you know, so people were like hanging the rapist hanging the rapist. And now if you read the book that Anup was talking about, it looks like I mean, there wasn’t much evidence that a rape event took place. So the argument for capital punishment is most often invoked in India in the context of violence against women. And you know, public opinion really favors the death penalty as a deterrent. According to you, how far has it actually served as a deterrent?

Of course, it’s both sexual violence against women and sexual violence against children that’s fueling the death penalty. And you see the legislative expansion of the death penalty with amendments to the box. So the IPC on this, and I think the women’s rights movement itself is very, very clear that the death penalty is not the answer. That the death penalty is not a detriment, because it misunderstands as to how and why sexual violence is produced in our society. And if at all, you want to have the Deterrents conversation, that the Deterrents conversation is much better served by the certainty of investigation and timely investigation and the certainty of punishment and abysmal conviction rates, show you what the problem really is. And also, secondly, that sexual violence in our society, both against women and children, by known people or acquaintances, that is fear of the stranger rape, and then are on which this harsher punishment conversation is built, just does not statistically play out, having the death penalty is only going to intensify the problem of under reporting. Anyway, Child sexual violence is massively underreported in our country, and to then tell survivors and their families that what testimony you could give could lead to the death of this person that you know, you’re so close to, just makes no sense. So even from the interests of justice for survivors, or the interests of the child, having the death penalty is such a meaningless move, right? Yes, it is. It seems like a good macho fast food solution that, oh, let’s just increase the death penalty and give it to everyone. But that’s not the social reality. It is giving into a certain kind of mob mentality. And nobody is saying that those who perpetrate child sexual violence should not be punished, they should be punished. But introducing the death penalty just ensures that less and less people report the crime.

So the debate on death penalty, you know, often hinges on what we actually think is the criminal justice systems objective, you know, whether it’s reform or attribution, you know, so retributive justice is the theory that, you know, when an offender breaks the law, the justice system requires them to suffer, and that the response to the crime should be proportionate to the offense, you know, something like an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth. If we imagine reform to be the system’s objective, then the state is supposed to help the offender to give up a life of crime and become a productive member of society. Now, in recent years, you know, we’ve seen that public sentiment is moving towards a retributive view of justice. So, you know, in your view, should the criminal justice system address the question of what good will it do or what bad has been done?

Look, first of all, I think there is a move towards over criminalization, both in terms of what we criminalize. And how much punishment are we seeing in our country, the multitude of examples of criminalizing certain activities, and you see that happening in terms of how criminal law is used in our country and the things that are getting criminalized, and then also saying that, you know, we need to increase punishments. And you see that especially in the context of sexual violence, and this idea that social problems, what are necessarily social problems can be solved by criminal law seems to have taken grip of our collective mentality, right that the fact that we criminalize something and we say, Oh, you will get this harshest punishment or, you know, life imprisonment or something. And that is a profound misunderstanding of how crime gets produced and why crime gets produced and what causes crime in society. Right. It misunderstands crime as and I would strongly urge everyone to read the work by the psychologist called

Craig Haney to show that those who commit crime are not just these bad apples with bad wiring. It’s not like this exercise of pure free will that you’re saying, You are alone and nobody else is responsible. And that’s true. And there’s incredible work in psychology now to show that even all of us what we consider action that we are doing based on our own free will, is not just freewill right, it is determined by a huge number of factors that in our life in our environment, in our context, that determine what we do, what we say what we think. And in that context, something like the death penalty assumes that you alone and nothing else, it was only a bad call on your part that caused you to do this right. That is it is your individual Free Will individual free error in judgment that made you do this. And there is no point to saying that, Oh, not everyone, in a certain set of circumstances, commit crimes. Sure, that’s absolutely true, right. But that’s just like saying that everyone would respond. In the same way to being interviewed for a podcast, I would react a certain way. And I would have a certain approach to this conversation and my comfort level or my discomfort levels would be a result of many factors of who I am, then somebody else might be a superstar at it and might be, this might be exactly the kind of thing that they are good at. But the point is to say that we all interact with various psychological, cultural, emotional factors in our lives, and what we do, all of those things has a profound impact on who we become and the kind of value judgments we make in life. And that psychological research. And I mentioned Haney is work just so that I don’t make it sound like this is something that I just cooked up in my head. We are not guided by freewill as much as we think it is. And then to think, what are the profound consequences of that research for criminal justice and questions of punishment and individual culpability? When you can see the consequences of that. And anyone who knows anything about our prison system will tell you that our prisons are not spaces for reformation. They are extremely violent, dark, opaque spaces. It’s a deeply inhumane system, and therefore we need to think about both what is it that is true of our society that is producing crime? And once that crime is produced? How are we treating people who have offended, and on both counts, I would think that we are miserably failing.

Yeah, Anup you’ve rightly pointed out how, you know, we tried to outsource social problems to the criminal justice system, you know, rather than deal with patriarchy, or you know, gender norms, you know, we just want to hang rapists. And you know, that is really not a long term solution.

Moving on to our last question, we’ll take a bigger picture. Now step back a little. So the state, of course, has a monopoly on violence. That’s how our society is structured. That’s how our nation is structured, at a philosophical level, should we give the state the right to kill?

The truth is, in our society, life is extremely devalued. And we need to locate the death penalty conversation in that broader context that we are no longer shocked by people dying of hunger, of extreme heat, or extreme cold of repeated deaths over floods, manmade disasters, natural disasters that we can plan, we are no longer shocked by loss of life, and then we’ve just become attuned to them. And we don’t hold the state responsible even in those circumstances. And then in that context, to have the conversation on punishment, and the state’s ability or the words, or its power to take life is a huge mountain to climb, to get people to realize that, that the state is playing with people’s lives, and the state should not have this power and the state, and that we all need to care about individual lives is a huge mountain to climb in our socio cultural context. And that’s often the difficulty of the death penalty debate. Then when you’re confronted with this routine, and large numbers of people dying for various reasons, the death penalty then sounds to seem like a five star problem. Because people are saying, Oh, what is this? You have three rounds of courts, you know, then you can go and file a mercy petition and then you can file you can challenge the rejection of the mercy petition on all of this, even then you have a problem. So that complexity exists, even on a broader scale. Should the state have the right to kill for me when crime occurs, the state and society has failed both the victim and the perpetrator, there is failure on both ends. And this connects back to what I was saying that when crimes are committed as a result of various things that have happened in the lives of those persons, the commission of crime is state and social failure. And we really need to acknowledge that the state cannot then say that, Oh, I will now side with the victim. And I will now only adopt that how something that the accused might have done is somehow not my problem, or I’m not even partially responsible for it as the state or society and why survivors or victims can have that sense of retributive justice or want that sense of revenge. I think that’s absolutely fine at an emotional individual moral level. But because crime is state failure, both on the perpetrator and the survivor. The state cannot follow a retributive system the state necessarily has to reform.

This was my conversation with Anuo Surendranath. And you’ve been listening to the ducks podcast. This episode was hosted by me Leah Verghese. If you liked the show, don’t forget to follow or subscribe to us wherever you listen to your podcast so that you don’t miss an episode. We would love to hear from you. So do share your feedback either by dropping us a review or rating the podcast where podcasts apps allow you to talk about it on social media. We are using the hashtag DAKSH podcast, it really helps get the word out there. Most of all, if you found some useful information that might help a friend or family member, share the episode with them. Especially thank you to our production team at made in India. Our production head and editor Joshua Thomas mixing and mastering Karthik Kulkarni and Project Supervisor Shawn Phantom. If you want to find out more about this topic, please have a look at the reading list in the episode description. And to get in touch visit our website DakshIndia.org that’s D A KSH India dot o RG Thank you for listening

RECENT UPDATE

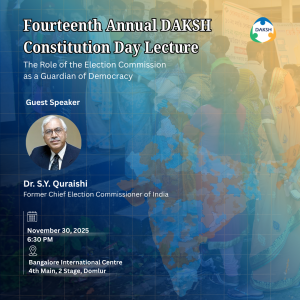

The Role of the Election Commission as a Guardian of Democracy | DAKSH Annual Lecture

-

Rule of Law ProjectRule of Law Project

-

Access to Justice SurveyAccess to Justice Survey

-

BlogBlog

-

Contact UsContact Us

-

Statistics and ReportsStatistics and Reports

© 2021 DAKSH India. All rights reserved

Powered by Oy Media Solutions

Designed by GGWP Design