Expediting Execution of Court Decrees

The Supreme Court in the case of Rahul S Shah v. Jinendra Kumar Gandhi and Ors. laid out a list of directions to ensure speedy execution of decrees in civil proceedings, and directed all the High Courts to accordingly make changes to rules relating to execution of decrees by 21 April 2022.

Deciding on appeals filed in a dispute that began in Bangalore in 1987 and which saw multiple connected legal actions, the apex court noted that the appeals demonstrated the ‘troubles of the decree holder in not being able to enjoy the fruits of litigation on account of inordinate delay caused during the process of execution of decree’. In order to appreciate why the Supreme Court laid down directions regarding the handling of suits and execution proceedings, it is necessary to understand how a single civil suit in this case led to a complex legal battle spanning several decades. While the facts of the case are appended to this article, the brief matter is that a case which started with a suit for declaration went on to see an injunction suit, a suit for possession, a suit for execution, an objection to land acquisition and claim for compensation, various actions before the High Court of Karnataka (appeals, a special leave petition, and multiple writ petitions), contempt proceedings, criminal proceedings, and a special leave petition and appeals before the Supreme Court. The cases ultimately came to a close with the Supreme Court dismissing the appeal and upholding the decision of the High Court of Karnataka.

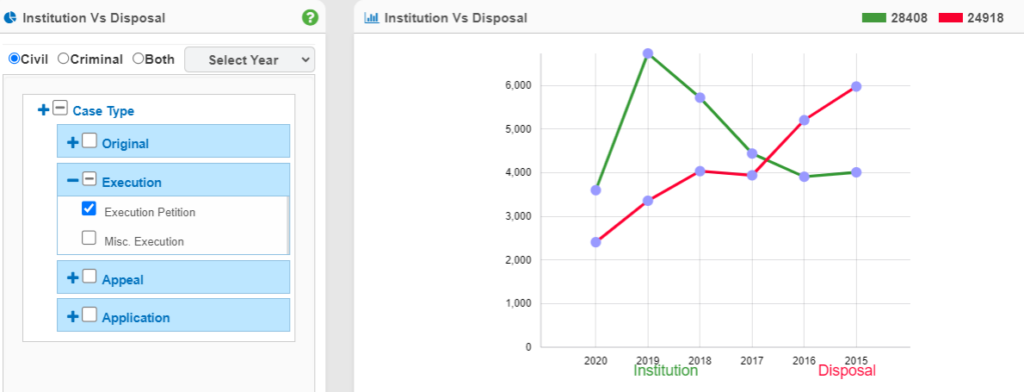

It is trite to mention that cases in India’s trial courts go through inordinate delays in adjudication. However, delays in execution proceedings are baffling given that the rights of parties have already been determined and a decree has been passed, the only thing remaining being parties adhering to what the court has directed. Yet, as per the National Judicial Data Grid as on 6 May 2021, nearly 30 per cent of execution petitions in Bangalore (the original location of the case being discussed) are pending for above three years, and 43.8 per cent are pending between one to three years. Let us also look at the trend of execution petitions being filed and disposed in Bangalore:

Figure 1: Institution and disposal of execution petitions in Bangalore as on 6 May 2021

Figure 1 shows that the number of execution petitions being disposed is steadily declining while the number of them being instituted has steadily increased (barring 2020 which has probably been impacted due to the COVID-19 pandemic). These numbers indicate the scale of the problem in accessing justice and demonstrate a need for clarity and direction on how execution proceedings can be made more effective.

Making note of the large volume of execution petitions in the country, the delays in disposing such cases, and multiple issues that may arise due to claims by third parties, the Supreme Court in the case of Rahul S Shah laid down the following directions with respect to suits and execution proceedings so as to do justice to the litigants:

- In suits regarding delivery of possession, the court must examine parties in relation to third party interest, including asking parties to produce documents and provide a declaration regarding third party interest.

- Where possession is not in dispute, the court may appoint a Commissioner to get an accurate description and status of the property.

- The court must add all necessary and proper parties to the suit so as to avoid multiplicity of proceedings.

- To aid proper adjudication, a Court Receiver could be appointed to monitor the property.

- The court must ensure that the decree is unambiguous and contains a clear description of the property and its status.

- In money suits, the court must on an oral application ensure immediate execution of the decree.

- In money suits, the court may at any stage of pendency demand security to ensure satisfaction of a decree.

- While dealing with the execution of decrees and orders, the court (a) must not mechanically issue notices based on a third party claiming rights, (b) should refrain from entertaining applications that have been considered during adjudication, (c) should refrain from entertaining applications that raise issues which could have been raised and determined during adjudication.

- The court should only allow for taking evidence in execution proceedings in rare and exceptional cases. It must only do so where the question of fact could not be decided by appointing a Commissioner or calling for electronic material with affidavits.

- When the court finds any objection, resistance, or claim to be frivolous or mala fide, the court (a) can direct the applicant to be put in possession, (b) may on the instance of the applicant direct the judgment debtor to be detained in civil prison, and (c) can also grant compensatory costs.

- In relation to Section 60 of the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908 (CPC) which deals with property that is liable to be attached and sold for execution of a decree, the language ‘in the name of the judgment-debtor or by another person in trust for him or on his behalf’ should be interpreted to include any person from whom the judgment debtor ‘may have the ability to derive share, profit or property’.

- The executing court must dispose execution proceedings within six months from the date on which the case is filed. This may be extended only by recording reasons for delay in writing.

- When the executing court feels it would not be possible to execute the decree without assistance from the police, it may direct the police to provide assistance. Further, if the court is informed of any offence against a public officer discharging their duties, such offence must be dealt with stringently.

- Judicial academies should prepare manuals and provide continuous training to court staff executing warrants, carrying out attachment and sale, or carrying out any other duties to execute orders.

The Supreme Court also directed the High Courts to reconsider and update their rules pertaining to execution of decrees to ensure the rules are in consonance with the CPC and the directions provided in this case within a period of one year. Further, the Court also encouraged the use of information technology tools to expedite the process of execution.

Facts of the case:

The facts of the case are that the owner of the disputed land executed sale deeds for portions of the property and later questioned the transactions through a suit for declaration in 1987. With the owner later executing a registered partition deed in 1991, the purchasers were restricted by an injunction from entering the property. While the suit was pending, the purchasers under one of the sale deeds filed suits for possession in 1996. The purchasers also sought transfer and mutation of the property in their names, which when declined, led to them filing a writ petition at the High Court of Karnataka. The High Court directed the khata to be transferred once the injunction suit was disposed. The City Civil Judge in Bangalore clubbed the related cases and in 2006 dismissed the suit for injunction, and decreed the suit in favor of the purchasers. The decree holders then filed suits for execution in 2007 as the owners had in the meantime sold the property through four sale deeds between 2001 and 2004 to other purchasers (‘subsequent purchasers’). While the execution proceedings were pending, a part of the property was sought to be acquired for the Bangalore Metro Project, which the decree holders objected to and sought possession. During this time, the owner had filed a first appeal before the High Court of Karnataka which went on to dismiss the appeal in 2009, and subsequently also dismissed a special leave petition by the owners in 2010. It was then found that while the cases were pending before the High Court, the subsequent purchasers had claimed compensation for the property that was to be acquired. The High Court in a writ petition then held that compensation could not have been dispersed to them and asked them to deposit the amount. The subsequent purchasers preferred an appeal against the order passed in the writ petition which the Division Bench went on to reject. Through another writ petition, the High Court in 2013 held that the purchasers were entitled to transfer of khata in their names. As the High Court’s order on depositing the compensation was not complied with, contempt proceedings were then initiated. The order passed in 2013 in the contempt proceedings was then challenged before the Supreme Court through a special leave petition that was dismissed in 2014. As the execution proceedings required parties to provide evidence of obstruction, while obstruction proceedings were pending, the owners filed criminal proceedings in 2016 against the decree holders. The criminal proceedings were stayed and later quashed in 2017. Various orders of the executing court then became the subject of writ petitions and appeals which were dealt together by the High Court of Karnataka through its common order dated 16 January 2020. The High Court of Karnataka amongst other things directed that the execution petition be disposed within six months and directed the judgment debtors to pay the decree holders costs of Rs. 5 lakh each in each execution petition. The case before the Supreme Court was an appeal filed by one of the subsequent purchasers wherein the Supreme Court upheld the order passed by the High Court and dismissed the appeal.

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author’s and they do not represent the views of DAKSH.

Shruthi Naik

RECENT ARTICLES

Testing the Waters: Pre-Implementation Evaluation of the 2024 CCI Combination Regulations

Not Quite Rocket Science

Administration of justice needs an Aspirational Gatishakti

-

Rule of Law ProjectRule of Law Project

-

Access to Justice SurveyAccess to Justice Survey

-

BlogBlog

-

Contact UsContact Us

-

Statistics and ReportsStatistics and Reports

© 2021 DAKSH India. All rights reserved

Powered by Oy Media Solutions

Designed by GGWP Design