I. The Big Idea: Change is not just technical, it is organisational

Large-scale digital transformation, such as that envisioned under eCourts Phase III, is a deep organisational change. For courts, this means rethinking not only how justice is delivered, but also how essential work is done, by whom, and with what tools. These shifts require more than new software; they require new roles, workflows, mindsets, and decision-making structures.

Change management, therefore, is the deliberate design of how institutions adapt to transformation, sustain momentum, and secure buy-in from every actor in the system.

II. Why Resistance Happens: the psychology and politics of reform

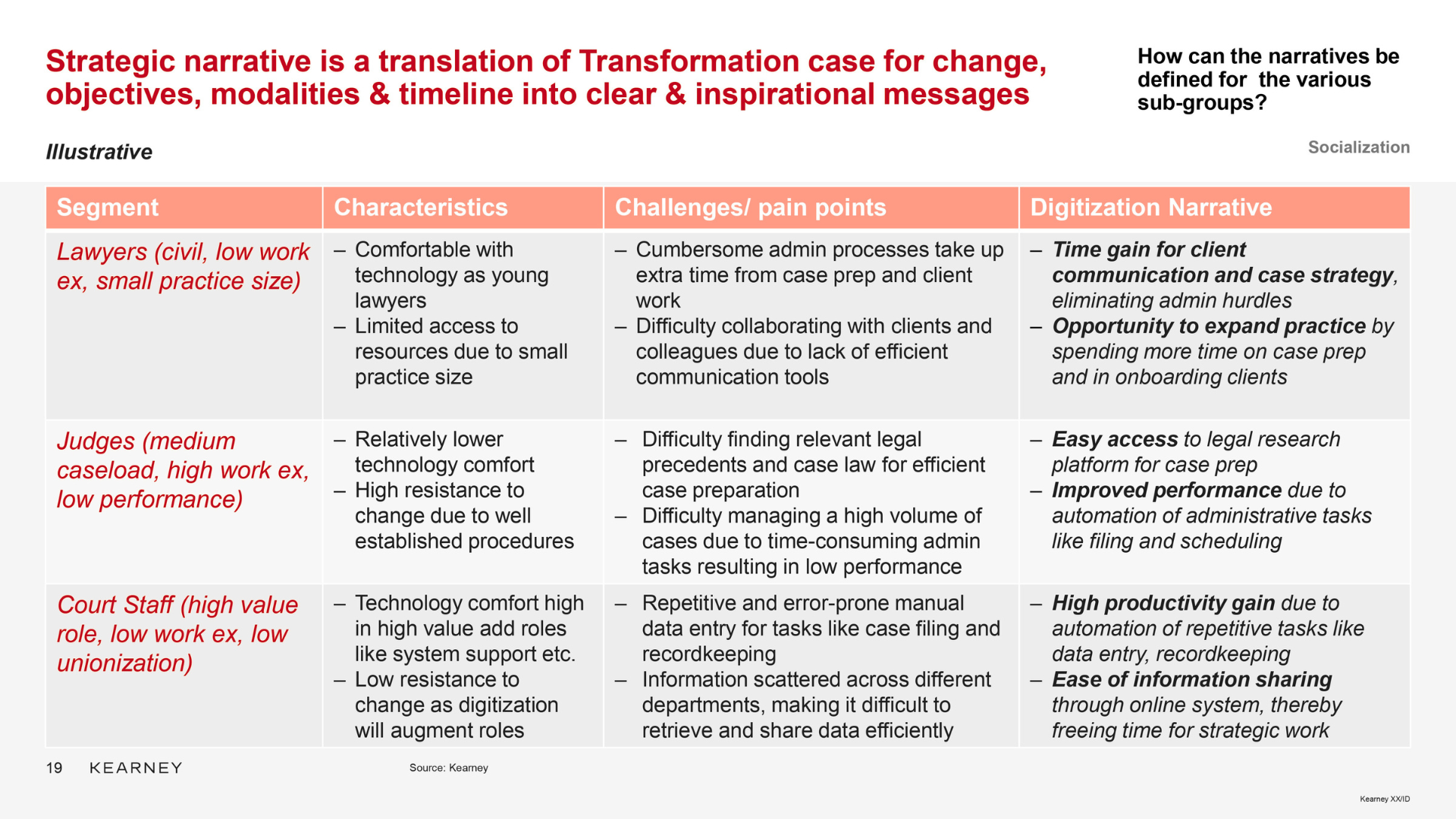

Resistance to change may often be a rational response to perceived threats, such as loss of autonomy, status, routines, or control. In courts, resistance can potentially come from:

- Registry staff concerned about unfamiliar digital tools replacing their routines or exposing inefficiencies,

- Judges worried about automation impinging on discretion or creating administrative burdens from untested systems,

- Lawyers fearful that greater transparency or simplification could impact their control or professional advantage, or

- Litigants and paralegals left out of the digital shift due to poor communication or usability

Limited capacity and lack of familiarity with experimentation further intensifies risks of quiet non-compliance or reform fatigue.

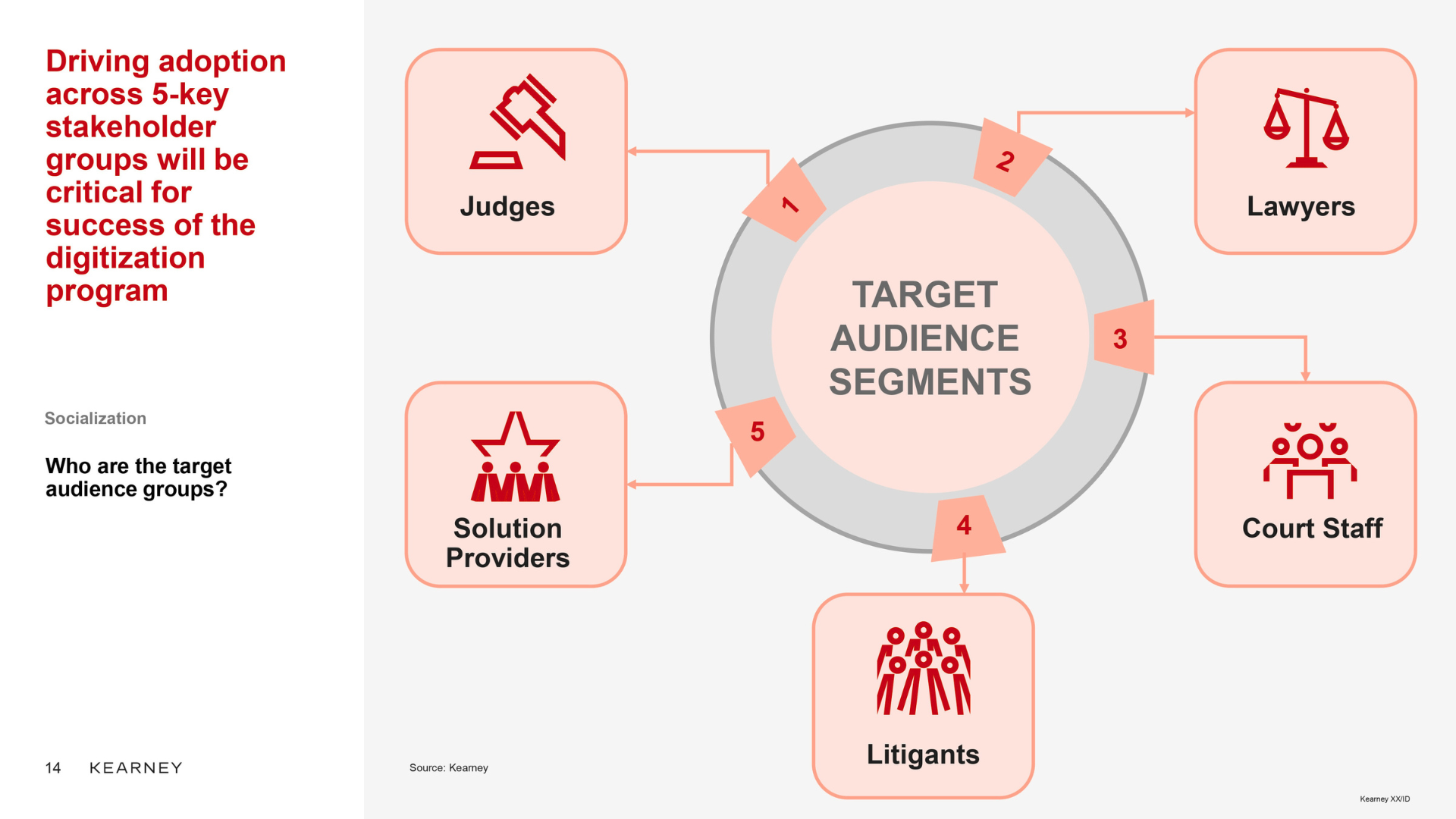

III. Who to Engage: a multi-level change strategy

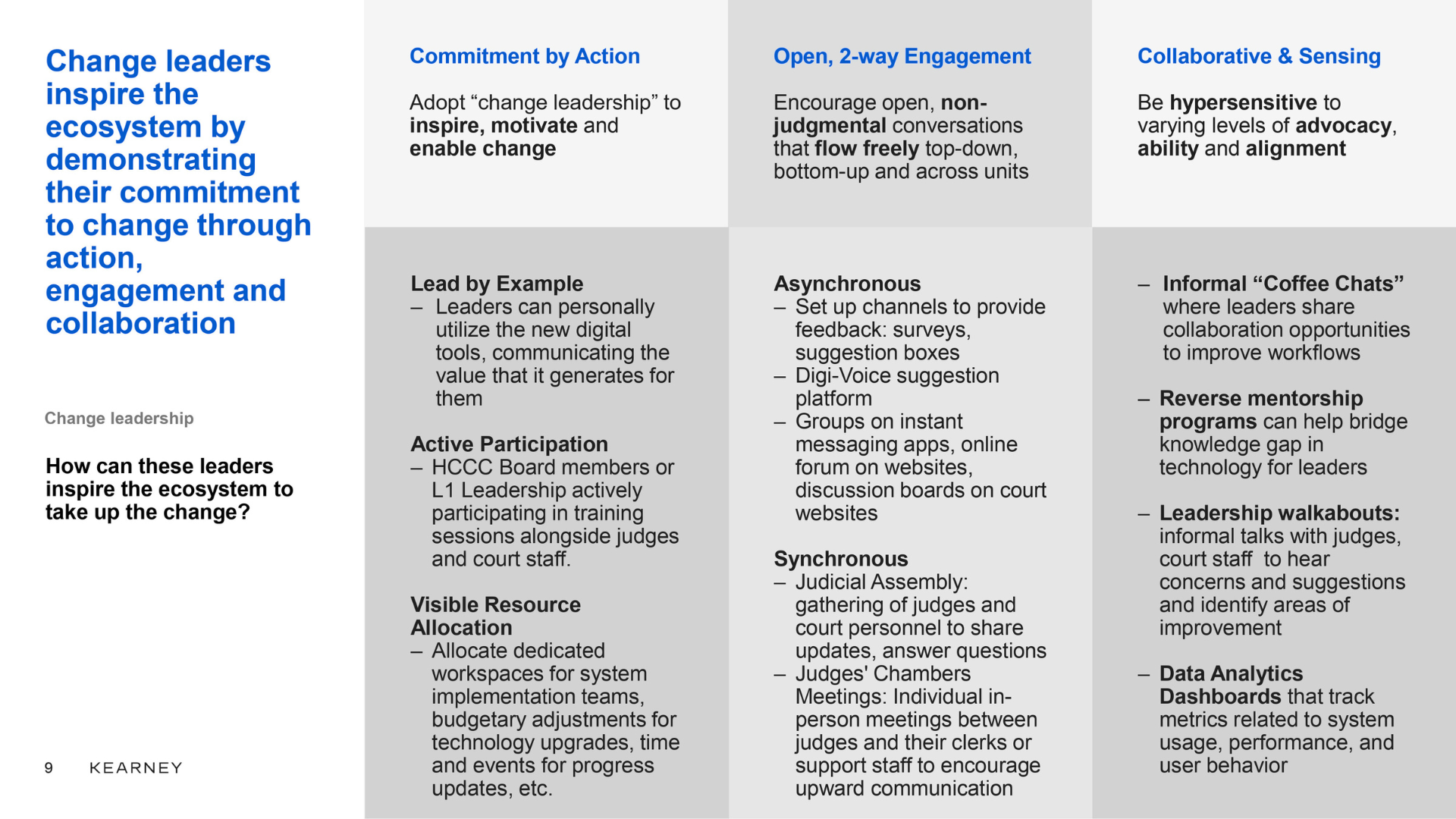

A successful change management strategy must operate both top-down and bottom-up:

A. Top-Down Actors- Chief Justices and Court Leadership: Must champion reform, lend it legitimacy, and signal that digital change is an institutional priority.

- eCommittee and High Court IT Committees: Should act as stewards of strategic clarity, technical vision, and structured feedback loops.

- Registrar IT & Registry Heads: Need to be empowered and resourced to coordinate execution, act as liaisons with the bar, and localise implementation.

- Registry and Support Staff: Often the first users of new tools; must be trained, consulted, and supported to shift workflows.

- Junior Judicial Officers: Can act as digital champions, pilot-test new modules, and provide honest feedback.

- Lawyers, Clerks, and Litigants: Critical to uptake; their pain points and perceptions will shape trust and long-term use.

A successful strategy recognises that reforms only succeed when those implementing them understand, trust, and benefit from them.

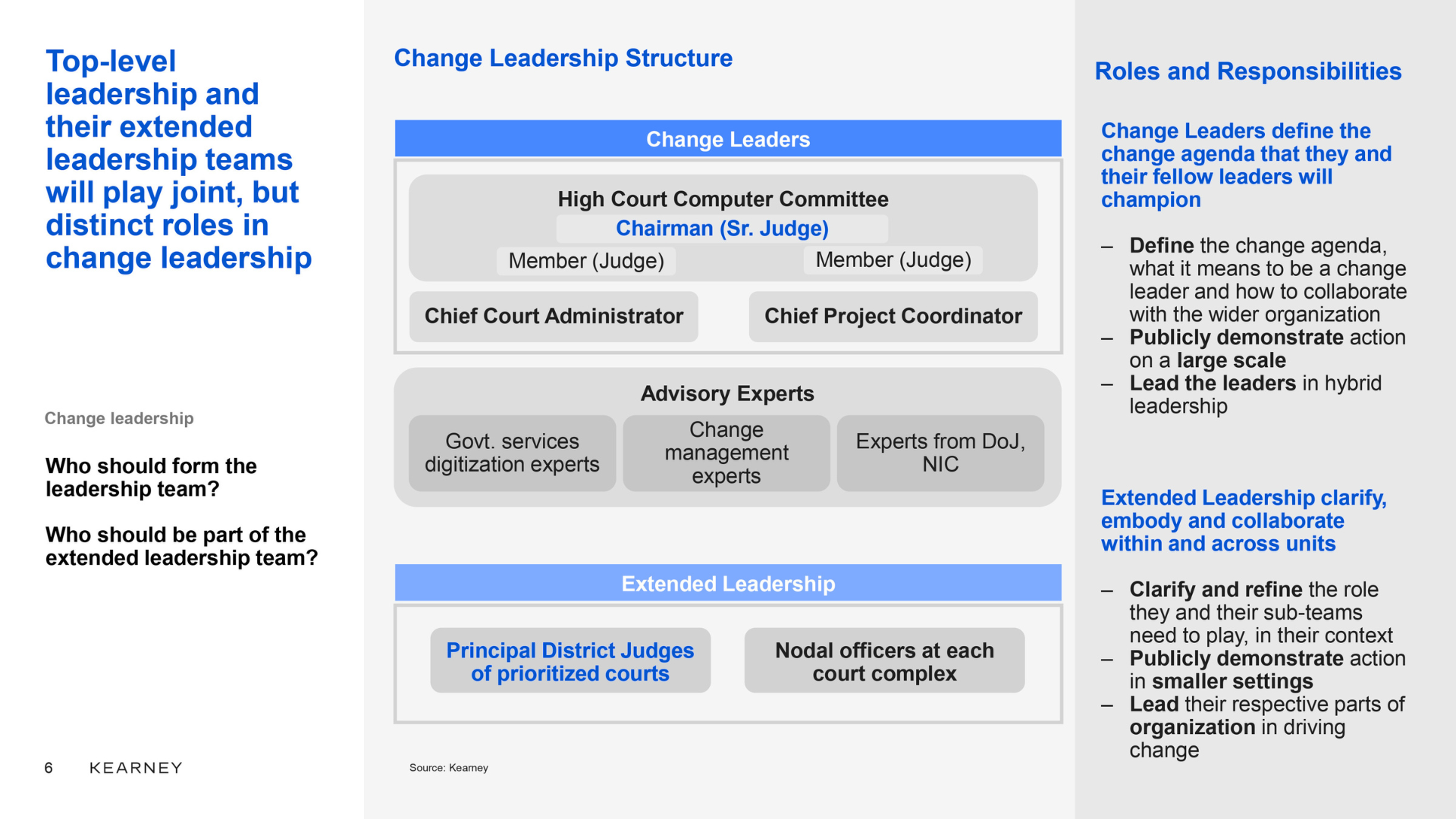

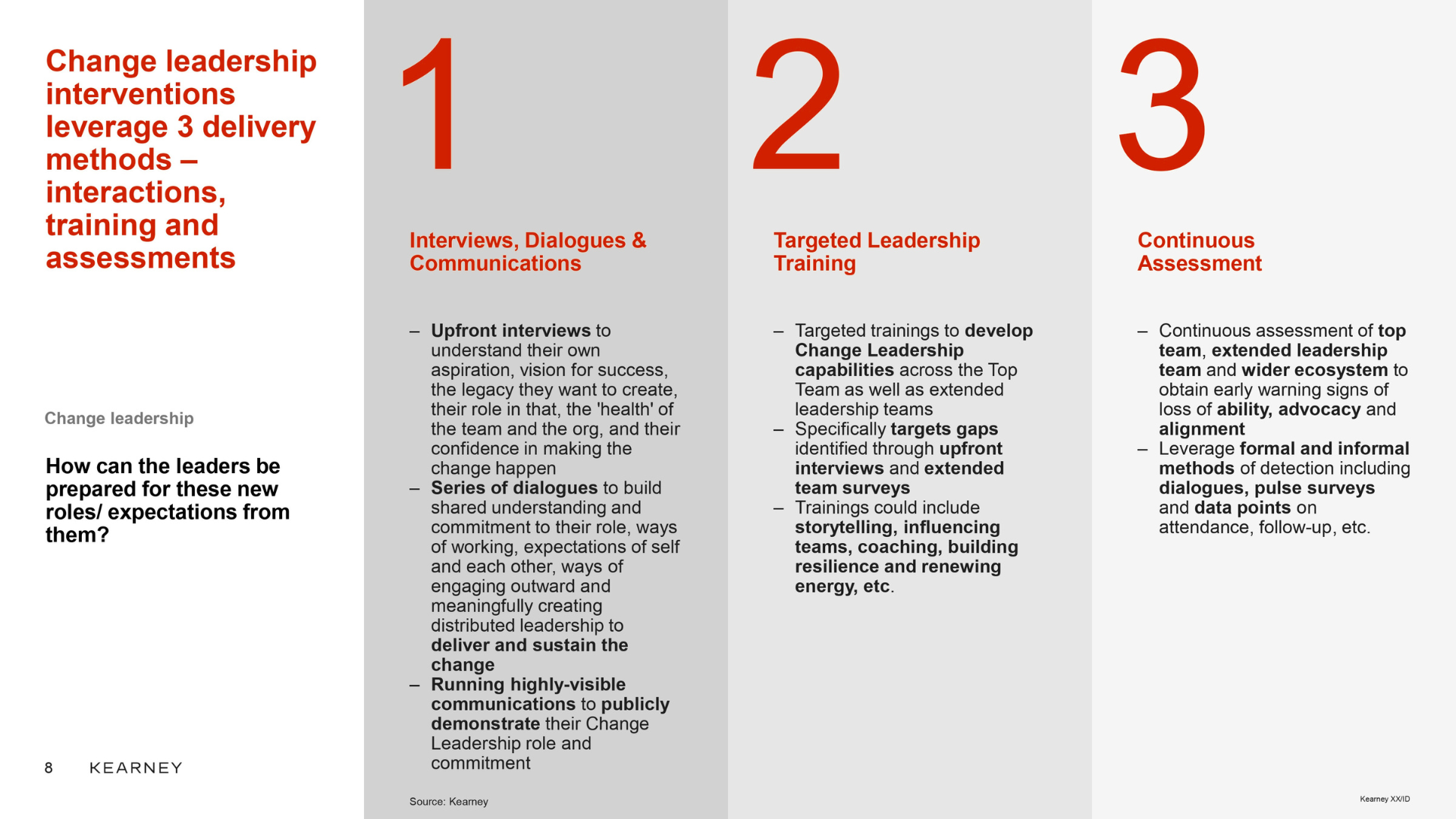

IV. Who Should Lead and How It Should Be Structured

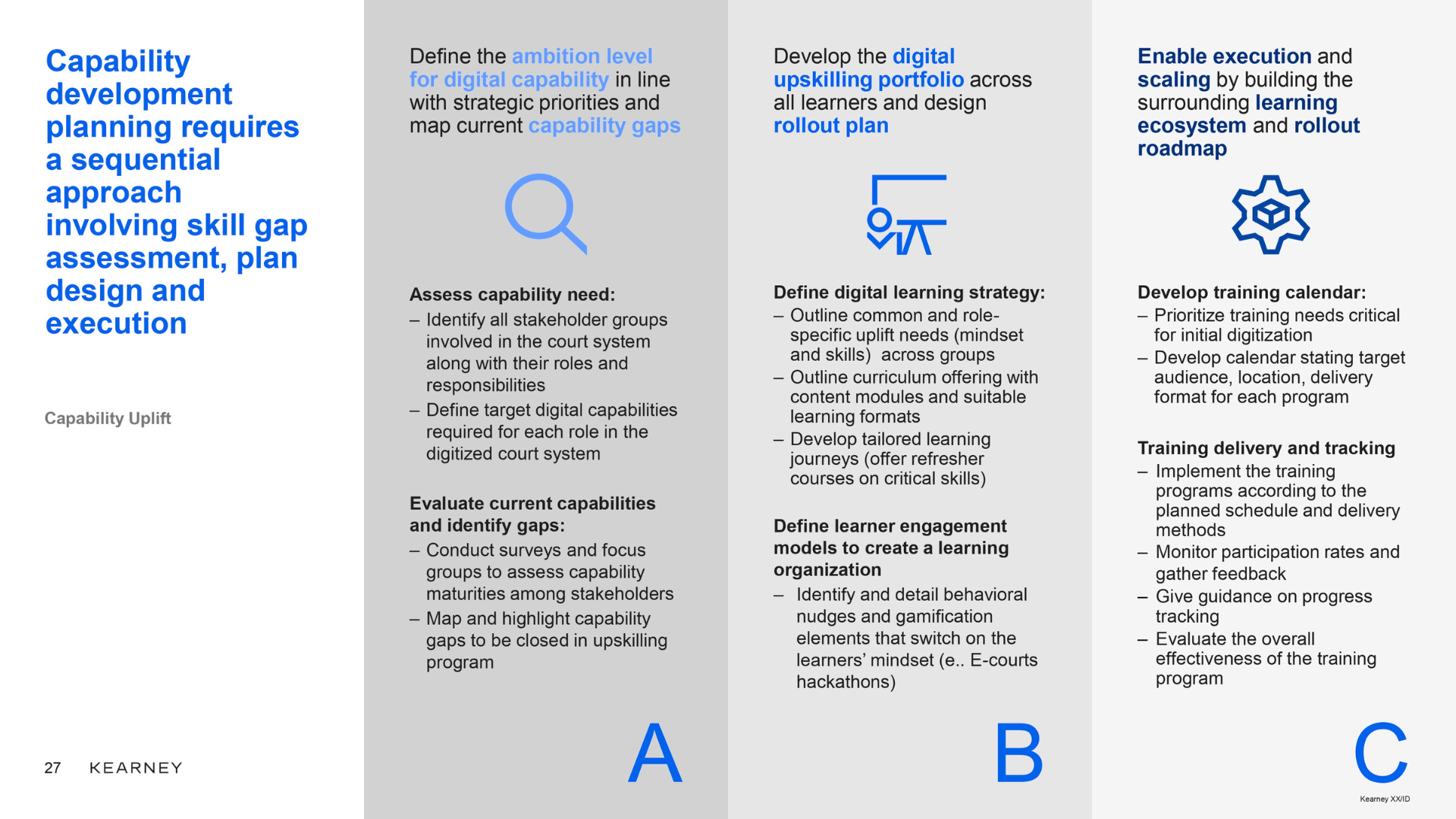

Change management must be owned and led, not outsourced or left to evolve ad hoc. It should be structured as a dedicated function, embedded in each High Court’s Computer Committees, with clear mandates and feedback responsibilities, which could look like:

| Component | Role |

|---|---|

| Change Management Lead | Oversees strategy, messaging, coordination, and reporting |

| Local Reform Champions | Selected judges, registry heads, or tech-savvy court staff to pilot and advocate |

| Training & Onboarding Cell | Conducts capacity-building, refresher sessions, and peer-to-peer support |

| Feedback and Pulse Team | Gathers feedback from internal and external users; reports usability issues |

| Communications and Outreach Cell | Develops public messaging, explainers, and awareness campaigns |

This internal structure could be supported by professional facilitation by public management experts, behavioural scientists, and service design consultants, who have worked in public sector transformation contexts.

V. Principles to Guide Change Management in Courts

A judicial change management programme should be anchored in the following principles:

- Legitimacy First: Reform must be seen as internal, not externally imposed. Judges and court leaders must voice support, set direction, and own the narrative.

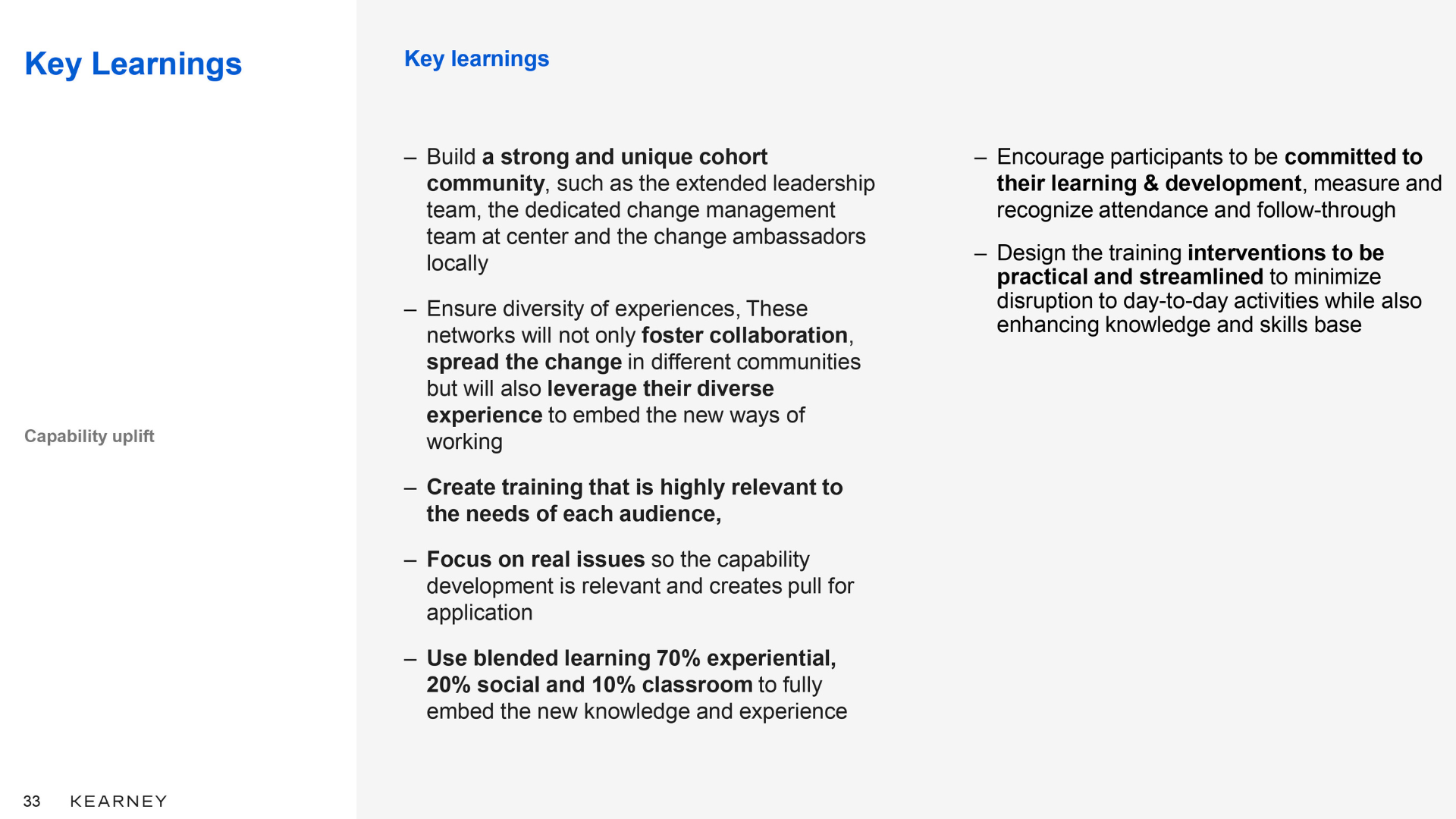

- Co-Design, Not Imposition: Change must be designed with the users, not for them. Early pilots, iterative design, and user feedback loops are essential.

- Incremental & Modular: Avoid “big bang” launches. Introduce reform in manageable modules, allowing people to build familiarity and confidence.

- Clear “Why”: Staff and users must understand the purpose of each reform: what problem it solves, and for whom.

- Recognition & Incentives: Celebrate successful adopters, highlight early champions, and avoid a punitive tone with slow adopters.

- Training Is Continuous: Build training into court calendars, not as a one-time orientation but as an evolving part of professional development.

- Transparency and Accountability: Share implementation dashboards with stakeholders. Let people see what’s working and where feedback is acted on.

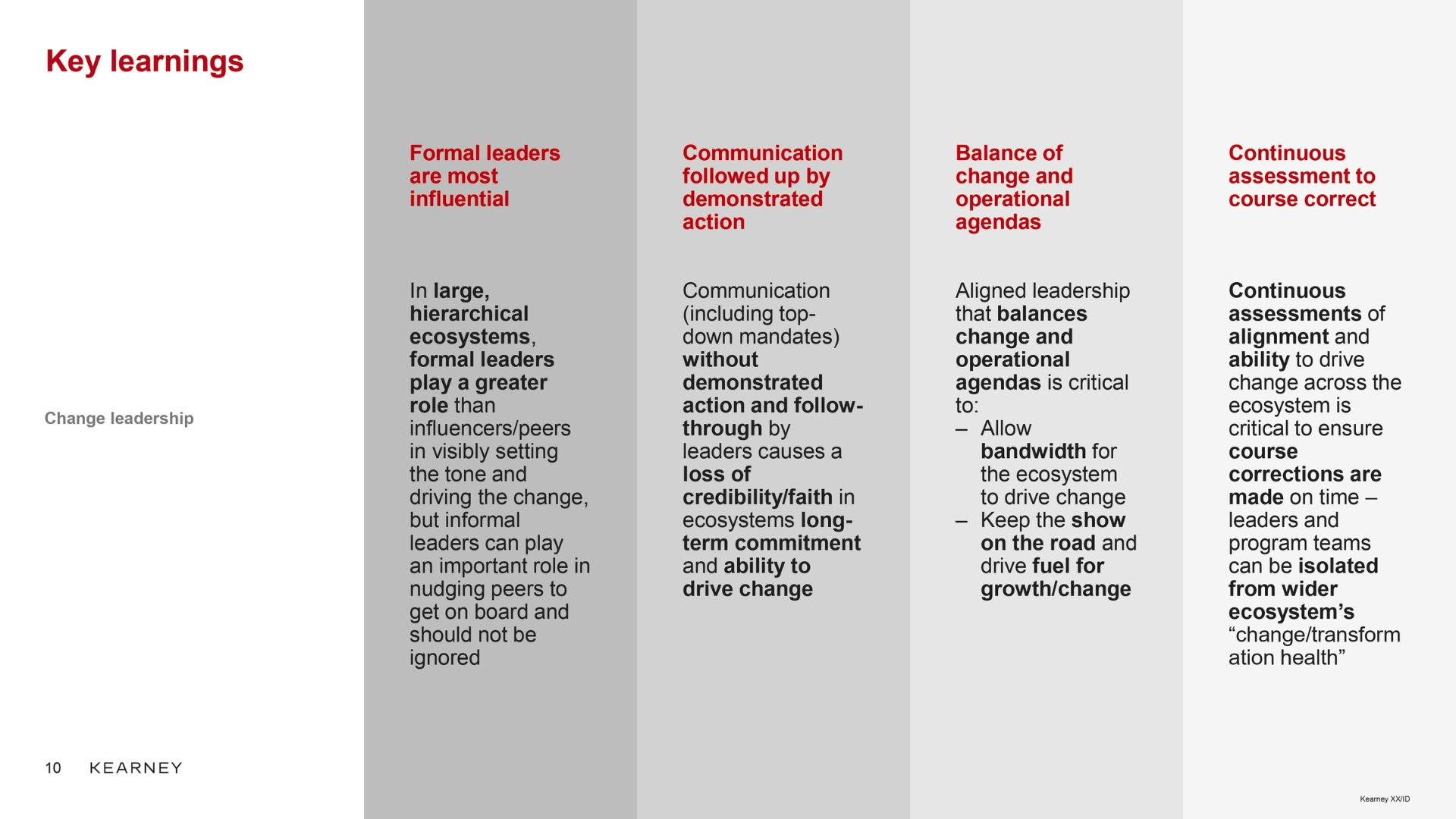

VI. Defusing Fears and Building Coalitions: Lessons from the Public Sector

- Passport Seva Kendra (MEA + TCS): Replaced a paper-intensive, discretionary process with a streamlined digital interface, while retaining government control. Transition was eased through training camps, co-location of old and new systems, and staff retraining with clear career pathways.

- Municipal Property Tax Reforms (Bengaluru, Pune, Hyderabad): Faced initial pushback from officials and taxpayers. Change succeeded when municipal officers were involved in re-coding processes and tax data was digitised with community help.

- eGramSwaraj and PMGSY Digital Infrastructure: In rural governance, change management was built into the rollout through state champions, digital trainers from the community, and incentives for transparent data entry.

- CBSE Onscreen Evaluation: Faced resistance from teachers and evaluators; pilot projects and collaborative tool design (especially error-proofing of input fields) helped build credibility.

These examples show that trust, transparency, and training are more effective than compulsion in sustaining reform.

VII. Why This Matters: Institutional Change Is Not a Side Project

Without a serious approach to change management, even the best-designed IT strategies risk non-adoption, workarounds, or quiet resistance. Courts are high-stakes environments where disruption can have legal and reputational consequences.

A change strategy:

- Builds legitimacy for digital systems from the outset.

- Reduces anxiety and minimises friction at the frontlines.

- Protects reforms from reversal or neglect.

- Makes the difference between compliance and commitment.

In effect, change management is the bridge between design and delivery and a critical investment for sustainable reform.

VIII. Further Resources

- Baker, D. (2007). Strategic Change Management in Public Sector Organisations. Chandos Publishing.

- Smidt, A., Balandin, S., Sigafoos, J. and Reed, V.A. (2009). The Kirkpatrick model: A useful tool for evaluating training outcomes. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, [online] 34(3), pp.266–274.

- Singh, K.D., Mani, R.N., Gupta, S. and Malhotra, S. (2016). 21 Jewels of Digital: Inspiring Transformation Stories of Indian Enterprises. [online] Notion Press.

- Goyal, A. (2021). Service Experience at Passport Seva Kendra: Case Analysis. Vikalpa: The Journal for Decision Makers, 46(4), pp.244–247.