Search and Seizure – DAKSH Podcast

- Abhinav Sekhri

- /

- The DAKSH Podcast /

- Search and Seizure with Abhinav Sekhri

In this episode, we explore the police powers of search and seizure with Abhinav Sekhri, a criminal lawyer and the author of the wonderful blog Proof of Guilt. During their investigation, law enforcement authorities like the police and customs and tax officials have the power to search our person and property, ranging from homes and godowns to laptops and other electronic devices. They can also seize objects they believe to be incriminating or relevant to their investigation. The exercise of these powers can create very distressing situations for people, especially if they are unaware of their rights. Abhinav helps us understand what the extent of these police powers are and emerging legal developments that may lead to reform.

If you like our podcast do consider supporting us with a donation at the link below: https://www.dakshindia.org/donate/

Show Notes

-

Support us by Donating.

-

Manaswini Rao. “Courts Redux: Micro-Evidence from India”. 2021. http://manaswinirao.github.io/files/rao_courts.pdf

-

Manaswini Rao. “Institutional Factors of Credit Allocation: Examining the Role of Judicial Capacity and Bankruptcy Reforms”. 2019. http://manaswinirao.github.io/files/rao_bankruptcy_and_judiciary.pdf

Anindita: Hi, you’re listening to the DAKSH podcast. I’m your host Anindita. I work with DAKSH, a Bangalore based nonprofit working in the area of judicial reforms and access to justice. In this episode, we will be exploring the police powers of search and seizure. During their investigation, law enforcement authorities like the police and customs and tax officials have the power to search a person and property ranging from homes and go downs to laptops and other electronic devices. They can also seize objects they believe to be incriminating or relevant to their investigation. As you can imagine, these powers can create very distressing situations for people, especially if they’re unaware of their rights. Today I will talk about this with Abhinav Sekhri, a criminal lawyer and the author of the wonderful blog ‘Proof of Guilt’. He specializes in upcoming areas of criminal procedure and is interested in the intersection of constitutional law and criminal process.

Hi Abhinav, welcome to the DAKSH podcast. Okay, so in this episode, we’re planning to do a breakdown of search and seizure laws in India, the extent of police powers of search and seizure and our rights as citizens in these situations. So without any further delay, I’ll get to the first question, where do the police get their search and seizure powers from?

Abhinav: The short answer is the Criminal Procedure Code. The long answer is, it may depend on what they are investigating. So if you are dealing with any ordinary sort of crime situation, you’re definitely not going to go beyond the Criminal Procedure Code. But if you are, let’s say, dealing with a case under the NDPS act for drugs or money laundering prosecution, then those laws end up having special provisions relating to search and seizure. And the rules of the game there may be different from what the case may be in ordinary prosecutions.

Anindita: So, what we see on TV usually is that, you know, a more conscious citizen would ask for a search warrant before the police can get in and search for anything. So I just want to know, in India is a search warrant always required for the police to search or seize?

Abhinav: Correct. So Indians will not show you that even though Indian TV will show many other things. Surprisingly, there have been two to form and thankfully, being very faithful to the fact that nobody really ever either gets or asks or demands for a warrant, especially when it comes to searches. And that’s a pretty faithful representation of what happens on the ground where warrants are not the norm. They’re definitely the exception as far as search actions go. The legal position on that is that while there is a requirement to get a warrant, there are also ample exceptions in the nature of emergent circumstances that basically allow for officers to go ahead and do the search action without a warrant. And the idea there is that the officer is senior enough to be trusted with using this power judiciously and when need really arises. And further that there has to be a written recording of, you know, the reasons as to why there was that sort of an emergent situation which required you to move in. So for instance, if he suspects that these people are gonna destroy a case property or something like that, or you’re acting on a, you know, very strict timeline, you don’t have the time to go and get a warrant. So that’s why the law gives you both actions. And in practice, at least from my limited years of experience, I’ve seen very rare cases where warrants are demanded or that search actions are later questioned on the ground, that there was no warrant preceding the search.

Anindita: Okay, so as a citizen, can I then ask for the justification because if I got this, right, if they don’t have a search warrant, they still need to record reasons. Can I ask for the reasons?

Abhinav: You may not, you won’t get a copy of the reasons then and there. What you may definitely be allowed to see is the authorization that the officer has. So I would say that yes, you can ask for the authorization. And what that means is that in some cases, that may be the warrant right. I mean, if you were to frame it the other way, if I am the citizen and I’m you know, sort of the police are knocking at my door, I would say yes, definitely ask for a warrant. So we know that a warrant may or may not exist, even if the warrant doesn’t exist, the idea is to ask for any form of authorization. So it may be that the person at my door is not authorized, his superior might be authorized. But he may have some sort of center junior officer, he can do that. But that requires an authorization. So you can ask them to show you that authorization that you have the power has been delegated to. So you can definitely do that. Obviously. I mean, let’s be very clear. That’s a really high pressure situation, you know, so expecting anyone to have the wherewithal and the presence of mind to stand up, you know, inattention just panned out saying, “Show me your authorization”, is not really how those interactions end up developing.

Anindita: Even culturally, I think we are not geared towards a situation where we question authority as much as maybe other jurisdictions.

Abhinav: I think very few people are, like I remember, you know, conversations outside where this was a kind of hypothetical thrown where I was in a room full of people, let’s say not in India. And the idea, the hypothetical that was thrown is, you know, suppose you’re walking down a garden path, and suddenly there’s an officer who just stops you and asks you to show your bag? Are you going to really tell the officer no, it was very obvious that everyone in the room were like yeah, I’m just going to say yes. Okay.

Anindita: Yeah, sure. We’ve all been stopped by the cops on the road. They look through our car. And there’s very little we can say, now we’re realizing even legally, there’s very little we can say to them. But in the exceptional circumstance where the police have a search warrant, what should we look out for? Like, can they just search my entire home if they have a search warrant? Do they have to specify what they’re looking for? Is there some limitation that they can have?

Anindita: Yeah, so ideally, you should check the search warrant for the level of specificity that it has in terms of either it has come for something specific in terms of a prosecution, then you are expecting to find items relating to that prosecution there. Or it will only say, Okay, I have certain rooms. So for instance, let’s say if you have tenants, so suppose they are not coming after you, but they’re coming after some tenants in your, like two storey house or something, then at least it may say that second floor or something like that, because you can even imagine a situation where you may not be the direct person affected by the search, but there might be ancillary connections between you and the search operation. But the few warrants that I’ve come across, you end up not really having that higher level of specificity. Usually, it’ll just say house, it won’t specify a room, like, I can’t remember a single warrant where you know, the level of room was specified. And it will say, it will bring the idea of what you want in the broadest possible terms. So for instance, I remember search actions in relation to corruption cases, where the idea is that we may find, you know, bribe money or unaccounted for cash. So they’re just basically use ABC, etc, etc, etc, you basically frame it as broadly as possible, rather than as narrowly as possible. So therefore, the warrant being very specific did not really help. Okay. Yeah.

Anindita: Okay. So what happens if that is, you know, later it is found that the reasons recorded for a search without a warrant was not justified? First of all, does that ever happen that the police’s search is found to be illegal? And if so, what happens then? Do you get your property back? Or will the stuff that was found in your house not be admitted?

Abhinav: So let’s break that up into two three things, right. So let’s imagine a situation where the police are going for a warrant. So that’s the first kind of scenario. If the police are going for a warrant that basically is an interaction between the police and the court, and the target of the warrant is not there, then the only pushback is possibly coming from the court? I have not been privy to these hearings, right? Because I’m usually a defense lawyer. I don’t work as a prosecution lawyer. So I’ve never been in that kind of a situation. But I must say that I have come across one instance where it wasn’t a search operation. But like, you know, it was, I mean, that’s a similarly placed issue where you needed judicial permission to do something for an investigation. And I came across an order where the judge had refused that permission. And the judge said that your grounds are frivolous. That basically is the court acting as some sort of oversight mechanism. So that’s number one. Number two is you have had a search, there has been a search operation, they have seized items, they may have seized them illegally. And then you have two options, right? You can either challenge the search then and there, or you wait, and then challenge the fruits of the search from being brought into evidence. So those are again, two different things. So you may be able to challenge the search, as actually, I think happened in one of the recent cases. I think it was a petition that was filed in Muhammad Zubair’s case where I believe a prediction actually came to be filed in respect to the search of his mobile phone, where they contended that that search was an illegal search, and the police ought not to be allowed to retain the contents of the phone. But again, that petition is pending, like many petitions, so you can’t really say much, but the idea there is that there is an illegality, and therefore the police ought to restore things back to status quo. And this is a very proactive posture for someone to take. It’s not usually what you would do. But you can ask the court because the powers of a high court or a constitutional court for that matter, it’s really broad. And they are broad enough to sort of pass certain directives regulating how the police go about doing their investigation. So that’s one kind of angle. The second kind of angle and I think this connects finally, to like, the second part of your question is that if you wait for trial, and you know what happens with the evidence, the material that they got in a search, if you make that the subject of your challenge by saying that, look, that search was illegal, and you can’t be allowed to look at anything after that. So on that, again, super technical so far, but this is the last bit of technicality that I will subject you to, again, there are two answers. So the general rule is that no, you will not be able to exclude that evidence, even if the search is illegal. And this relates to a really funky sort of legal rule called the idea that the fruit of the poisonous tree are not poisonous. So the fruits can be admitted, even if the tree was poisonous is sort of the legal jargon for this. But this is again, the general rule. And it is subject to exceptions. So for instance, there are some acts primarily the NDPS Act, the main law relating to drug prosecutions, where courts have held that you know, because of the seriousness of the offense, and the fact that mere possession of certain items that may be the result of the search in and of themselves become offenses, that has a higher degree of compliance required by law enforcement agencies. And if it can be shown that the legal procedures were not fully followed in respect of that search operation, then you can try and get that evidence out. And this is most developed in respect to searches of a person. So for instance, let’s say, you know, if you will frisked. And there’s a very strict sort of set of regulations that they have to comply with in respect of how they go about it. And there’s a long line of cases that is continuously held, that even though the norm might be that evidence obtained illegally is still admissible, because of the special nature of these kinds of cases, we will not allow that to happen.

Anindita: Because I think the probability of evidence being planted in drug cases is high. So I guess that’s what you mean that and having planted it directly leads to the offense, having already been committed.

Abhinav: The amount of steps that you have to travel from the recovery of that item to a conviction is very few. Whereas in other cases, you know, that might become one factor in a chain of facts that ultimately leads to a conviction. So I think that’s what prompts the court to go down that path.

Anindita: Okay, so from what you’re telling me so far, I get the picture that largely the police and law enforcements have the ability to search and seize, and we have very few real limitations, at least in terms of procedure. Am I correct? Would you agree with me?

Abhinav: Yeah, I mean I do agree with you. We are stuck in a legal system that is, you know, this is something that the current government is actually insisting upon all citizens to share the colonial baggage. And I think the place to start that is by shedding the massive colonial baggage that is inherent in the criminal codes, especially the Criminal Procedure Code, even though that might be a 1973 legislation. For all intents and purposes, it is actually just copying provisions that were there from the 19th century, at a time when there was no question of the government being limited in its powers. So the idea of law today is, especially when you come to criminal procedure, the idea is to have laws that will limit government power. Whereas if you go back in time, and if you look at a regime where there is no democratic rule, there is no constitution to sort of limit government power, the idea of laws is just technical, right? So it’s sort of to give you clarity as the administrator that this is what you can do. There’s not a limit. And that’s a fundamentally different way of looking at the nature of the powers.

Anindita: No, I agree with you because we really think about the Criminal Procedure Code was meant for the British to be able to carry out its agenda and now we’re still living with the same laws but the British have been replaced with whichever government might be in power. But the interesting thing is we also have our Constitution, which is mostly a modern invention. I mean, of course, there’s lots of criticism about the Constitution also having a lot of colonial baggage but not quite as much as criminal law. Through all the episodes of our podcasts that we’ve been recording, we’ve been looking at how rights help us limit what the government can do to us. So I just want you to contextualize how the rights in our constitution helped protect us where clearly the Criminal Procedure Code doesn’t.

Abhinav: So just, two thoughts on that. And like, I’ll go into a little bit of a digression here. I think before rights, it’s sort of important that we realize that there is a fundamental difference between pre-1950 and post for two reasons. And the biggest reason for that is that the fact that there is a constitution that says we, the people of India, give to ourselves a nation means a big deal from what it was to what it is today. And that is the foundation of everything. And since that is the foundation of everything that sheerly, it is transformatively changing what you look at the law, like like how you look at the law, rather, and there’s a lot of writing on this in terms of just the history of the courts is to go back to what you were saying earlier, what do we think of the criminal codes, there is no need for the government to claim legitimacy in terms of any of these laws, and then it’s a colonial power, right? It has power, that’s it, nothing more matters. Today, that’s not good enough. Today, the government can go ahead and pass a law that says, okay, they will be hand scarred for theft, there is a reason for that. The reason for that is not just that we don’t like it, the reason is that it’s something that you will not be able to do in a democratic setup, because there is a requirement for legitimacy in your laws. So having said that, one way that that gets described, is through the fundamental rights, as you mentioned. So we sort of come to it as an expression of this idea that there are the individuals and citizens and within the constitutional framework, are people who have dignity that can’t be trifled with by the state. Within the context of self incrimination and like search seizure, the right to life, I think what becomes relevant is articles 20 and 21. Most importantly, I think article 21, which deals with the right to life and personal liberty is obviously the most directly affected, fundamental right, in this kind of a setup. You could even say that seizures would have affected the fundamental right to property, but there is no fundamental right to property anymore in the Constitution. But when you speak of the idea of the right to life and self incrimination I think self incrimination seems to be the intuitive answer that you’re forcing me to sort of become a witness. Right, you’re forcing me to go ahead and implicate myself.

Anindita: That’s article 20. Right?

Abhinav: Yeah, that’s article 20, sub clause three. But the intuitive answer is actually, if you scratch the surface, it doesn’t hold for one very textual and very lawyerly stupid reason. And a more fundamental reason as well, the textual stupid, lawyerly reason is that our constitution actually doesn’t give everyone the right to sort of claim self incrimination, the Constitution itself says no person accused of any offense. So until you are accused of any offense you don’t have any claim to make.

Anindita: But before you go ahead, just one technicality. So let’s get this straight. So article 20, has a right against self incrimination. And that means that you can’t be forced to reveal something that goes against you in a criminal proceeding. When you say that only an accused has this right does this mean that the police should have already completed its investigation and named you in a charge sheet for you to be considered accused? What does it mean to be accused?

Abhinav: Yeah, again, lots to unpack there. I know, I said that before as well. It’s like poetry, right? I mean, that’s the problem, like one sentence has been interpreted by these countless judgments. It is like you’re dealing with a school poetry project. But anyway, on the issue of accused, the idea is that there must be what is called a formal accusation against you. And short answer, no, there need not be a chargesheet against you. But in some cases, and this is by way of complete, like legal skullduggery, there are actually contexts in which courts have said that no, you actually need the inquiry or investigation to be complete. For us to you know, be sure that you are actually accused of an offense, and we can ignore that. But for your question, yeah, you don’t always need a chargesheet against you. And in the majority of cases, the fact that you’re named in an FIR or the fact that you’re even if you’re not named the fact that you’re a subject of an FIR. Suppose you’ve gone ahead and taken anticipatory bail and you are on anticipatory bail, that’s pretty much a clear sign that today you are an accused. And so you can claim article 23 rights.

Anindita: Yeah, no, fair enough. So basically, we understand that the right against self incrimination is fairly limited. So let’s go back to what you said earlier, which is that the thrust of your defense would be article 21?

Abhinav: There is another thing, right? So this was the technically stupid lawyerly objection, there is the more foundational objection, which is that if you think about search and seizure, you’re actually not doing anything. So the idea of self incrimination is that you are forcing me to give evidence. If the police are barging through your doors, the police are doing all that, they aren’t asking you for anything. So they might then turn to you with a lock and ask you to open it. That is separate. But broadly, a search idea is that the police are going ahead and getting whatever they want. As long as that is the long and short of the search and seizure action, you can’t really say that the right against compelled self incrimination has anything to do there. Because well, technically, it doesn’t like you’re not being asked to do anything. You can just sit by while the police rummage through everything that you own and hold, like hold dear to yourself.

Anindita: But so you’re saying that if there is no positive action that I have to take for the police to conduct the search, then this right wouldn’t be attracted. But what about things like passcode to phones? I mean, the cops ask us to actually put in a passcode so that they can see our phones, that would be self incrimination? Yes, no?

Abhinav: Lawyer answer: There are petitions pending on this across courts, then there is a judgment of the Karnataka High Court that has said no. There is a order of the Kerala High Court that has also said no, it’s not a judgment. It’s an order in like some long issue where two courts have said no. Delhi high court, issue is pending. There is then a PIL in the supreme court asking for guidelines in respect to these issues. So legal position.

Anindita: So the jury’s still out on that one.

Abhinav: Yeah. So far. I mean, if you will, within Karnataka, then I would say that the police have strong legal basis to ask you to give them your passwords. The issue there is that, funnily enough, this is a question that a lot of countries are grappling with, obviously, and very few of them have clarity in terms of what to do about it. There’s so many small, small, small issues that you can make up in this kind of scenario, right? So for instance, what if it’s a passcode? What if it’s a pattern? What if it’s a thumbprint? What if it’s a face scan? Already that one small question of opening up the phone, you can have four different variations. And technically, if someone just takes my phone and puts it up in front of my face, have I really done anything like the mere fact of me sitting there? And the idea there is this, this issue of what it means to incriminate yourself is actually a pretty big question across jurisdictions. And India also doesn’t have very clear answers to this, what India does is again, adopt some sort of a bright line rule in the sense that we say things that are akin to giving a sample of something for an investigation, so for instance, if the police asked you to give a blood sample or a fingerprint, anything that by in and of itself cannot be evidence, right? The blood sample has to be compared with something recovered, the fingerprint has to be compared with a fingerprint. So anything that has this comparative idea, that won’t be incriminating, because in and of itself, that can’t be evidence.

Anindita: Just to understand this better, can you give me like a clear example of something that self incriminating?

Abhinav: Imagine the police have asked you to give a confession by forcing you to give it, not simply asking you because the police can ask nicely, but what if the police beat you up? And then they give me a confession. Otherwise, you’re not going out of here with all your nails, the mafia type of thing that they show in movies that that’s supposed to be the kind of valiant police, that we’re all supposed to stand up for. That you’re beating up someone, especially when there is obviously a terror attack. So that is the only way to crack that crime. But that is a compelled coercive confession. And that is self-incriminatory. That is as clear as it can get which brings us to article 21, which and article 21 I would say that today is definitely the go to logic for dealing with searches from an individual rights standpoint, because especially after the supreme court’s judgment in Puttaswamy where privacy inheres in article 21 right and there cannot be a more clearer idea of privacy than being safe inside your own home. And the government having very good reason to intrude upon the privacy of your home.

Anindita: Right, before you go forward, just for the context setting for our listeners is that the right to privacy doesn’t exist in written form in our Constitution, but has been founded to exist within the realm of article 21, the right to life, which is a part of our Constitution in the Puttaswamy judgment.

Abhinav: So what Puttaswamy does is, actually it doesn’t only say 21, it actually goes ahead and says that privacy is inseparable from the idea of the individual in the Constitution as it is today. In Indian democracy, privacy is part of who you are. So it is part of when you are exercising your right to free speech, your right to freedom of movement, your right to life, and even like article 14 for that matter, which is the right to claim equal treatment from the law. So the idea is that, you know, it is a fundamental facet of being a person, given just the high pedestal at which privacy had been placed, you think that that really would require stronger grounds, stronger tests, stronger justifications for the state to go ahead.

Anindita: And yeah, because I still have questions about it. I mean, is it a facilitative right, is it right in and of itself, we’re very confused about this.

Abhinav: But it is supposed to be right in and of itself. The idea was that the court said this. The court said that look, what we’re doing today is we’re identifying this, but all these battles regarding its boundaries will be fought later. And the court did acknowledge this right that it is not going to mean that the state can’t do searches and seizures. But the idea is that within a setup where you don’t have any idea of privacy, which is actually really relatable to the pre-colonial and post-colonial, you couldn’t really turn around beyond the text of the Criminal Procedure Code earlier to say that look, you have not followed XYZ, so what you’ve done is wrong. Today, even if there was no XYZ requirement to respect my privacy within the code, I have the ability to go ahead and tell a judge that they have violated what is a fundamental aspect of my dignity, by going ahead, barging in. And you can imagine various ways in which that can blossom like going ahead. Obviously, we have already traveled five years ahead from 2017 and yet it is to blossom in any of those ways. But one can always hope. So one way in which this has happened, actually, funnily enough, is illegal surveillance of phone conversations. Mere illegality is different from constitutional violations. And so if you are saying that someone has breached the right to privacy, then maybe the fruits of that poisonous tree are also poisonous. And so you have had judgments of high courts, specifically the Bombay High Court that has said that surveillance that was done contrary to the terms of law, whatever, you know, messages, etc, that you got, you will not be able to rely upon them in evidence. So it’s still a one off, but I think you can imagine an action based on privacy materializing in many ways. One of these is obviously just a simple thing at trial by saying that, look, you cannot rely upon anything that is illegally taken from me. It can even go in so far as requiring greater specificity in terms of you know, what do you come for? Like, even in my house, why do you need to go to all of my house, like, Who gave you the right like, I understand that this is relevant for your prosecution. But surely, you will have done your homework. If you have, let’s say, come here on some basis, then there has to be basis for you to show as to why you need to rummage everything in terms of every drawer, every sock drawer, every locked room. You have to give reasons for that. And I think it will all come to ahead very quickly in the context of mobile phones. The idea that we are carrying our lives in our mobile phones is really the shortest way to sum it up. Our home may not have as much relevant about us, especially you know, given the kinds of lives that we live, where we don’t even have digital credit cards, we do UPI transactions. Our physical realm may not have as much importance about us as they may have on a mobile phone in our hands. And I think the lack of clarity surrounding what the police can do in respect of mobile phones, not only in respect of persons who are accused, but anyone for that matter. For instance, if we go back to the idea of there being a house and there be just one person who’s relevant to the investigation. Today, it’s very common for the police to ask everyone in that room to just sort of, you know, show me your phone and all that of that, I would say that post the idea of the right to privacy being entrenched in the Constitution, you can imagine stronger challenges. It hasn’t yet happened, because at least in the context of investigations, the courts have so far concluded that, you know, the investigative interest ought to be paramount. But I think that it’s not impossible to imagine that a different court might come to a different conclusion on that.

Anindita: To end on a positive note, though, through our conversation, what I feel like is, for a long time, the debate surrounding search and seizure laws was limited to the Code of Criminal Procedure, or whichever other act was relevant for the investigating authority and the kind of crime that was being investigated. But the moment we have this Puttaswamy judgment and a more constitutional view of this problem, it opens up more avenues of challenging how search and seizure happens. And we no longer have to stick to the code and we don’t have to just check if the police followed what the Code of Criminal Procedure says. We can ask questions outside of it, because now we’re looking at the Constitution and what is privacy and what is truly the meaning of dignity and the right to life. Looking at every law almost through the point of view of the Constitution makes it easier for us to look at what is the real purpose being served?

Abhinav: Yeah, this is going to be a really exciting area of law, like going forward. I mean, a note of hope, and a note of caution. And I think the note of hope is obviously that for a lot of these issues, especially search and seizure, and you know, the limits of intrusion by police agencies and state agencies, I think the paradigm shifted with Puttaswamy. We have to acknowledge that, what that means, the way of seeing it has changed. For a court to, the second step is for courts to actually confirm that this is the right way of seeing things, you have to start seeing it this way. And that is a process. And the process has two-three different issues. One is obviously people who have the ability to go will go, because the sad truth is that there will an overwhelming majority of the targets of criminal prosecution, the people who are actually subjected to these searches and seizures, will never have the ability to actually speak that language of rights, they will be at the mercy of the police agencies, they will not have the wherewithal to file those petitions and courts, and to expect the benefit of that paradigm shift to reach them. I think that is the actual target to hope for. Right, that someday that can happen. And that can only happen by way of an instrumental process where at every search where people have the ability and judges when they are dealing with searches, it begins with asking questions, and it begins with disposing of questions that are asked. So for instance, the many petitions that remain pending, like unless those questions are decided, unless those questions which are being asked are taken care of, there is no expectation that you can legitimately have that, you know, the officers will get trained in a certain way over a period of time. So maybe not this year or next year, but maybe five years from now, you can hope for some improvement in terms of the basic minimum being not you know, at the floor, but maybe at one meter in a bar that goes up to 20 meters. And I think even that’s a very, very big thing, because that one meter difference is going to make a difference to the lives of countless countless people. And that’s a much more sustainable change rather than one person going to court and getting a relief in his or her matter. And that’s what we should target for, a target that will really make a difference to all those people who will never have the ability to go to court to enforce their rights.

Anindita: That’s exactly the kind of positive note I was hoping to end on. So, thank you Abhinav so much for all your time and thoughts.

Abhinav: My pleasure, Anindita.

Anindita: That was my conversation with Abhinav Sekhri, and you were listening to the DAKSH podcast. If you enjoyed the episode, do consider supporting us with a donation. The link is in the show notes below. Creating this podcast takes effort and your support will help us sustain a space for these quality conversations. To find out more about us and our work, visit our website dakshindia.org. That’s D-A-K-S-H india.org. Don’t forget to tap, follow or subscribe to us wherever you listen to your podcasts so that you don’t miss an episode. We would love to hear from you, so do share your feedback either by dropping us a review or rating the podcast where podcast apps allow you to. Talk about it on social media. We are using the hashtag DAKSH podcast. It really helps get the word out there. Most of all, if you found some useful information that might help a friend or family member, do share the episode with them. A special thank you to our production team at “Maed in India”. Our production head Niketana K, edited, mixed, and mastered by Lakshman Parshuram and project supervision by Sean Phantom.

RECENT UPDATE

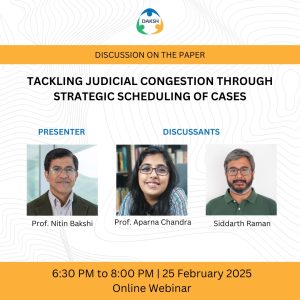

Webinar on Tackling Judicial Congestion Through Strategic Scheduling of Cases

Year in Review: NCLT and NCLAT Under the Supreme Court’s Microscope

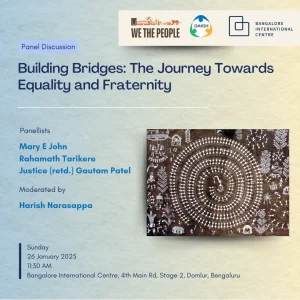

Building Bridges: The Journey Towards Equality and Fraternity

-

Rule of Law ProjectRule of Law Project

-

Access to Justice SurveyAccess to Justice Survey

-

BlogBlog

-

Contact UsContact Us

-

Statistics and ReportsStatistics and Reports

© 2021 DAKSH India. All rights reserved

Powered by Oy Media Solutions

Designed by GGWP Design